“I can’t do this forever.” So says Rio Hiiragi, a nineteen year old pop idol who is acutely aware of the youthful constraints of the industry she is a part of. The pragmatic centre of Kyoko Miyake’s empathetic and troubling documentary on teenage pop idols and their largely middle-aged male fan bases, Rio provides a sensible outlook in a world that is equal parts outlandish, frightening and fascinating.

There are thousands of young girls in Japan striving to become idols. Very few ascend into the upper echelons of national fame, and are instead eking out performances in idol cafes or small venues, trying to build up their visibility. Yet even these lower level idols have their devoted fans, and most are men between the ages of 20 and 50.

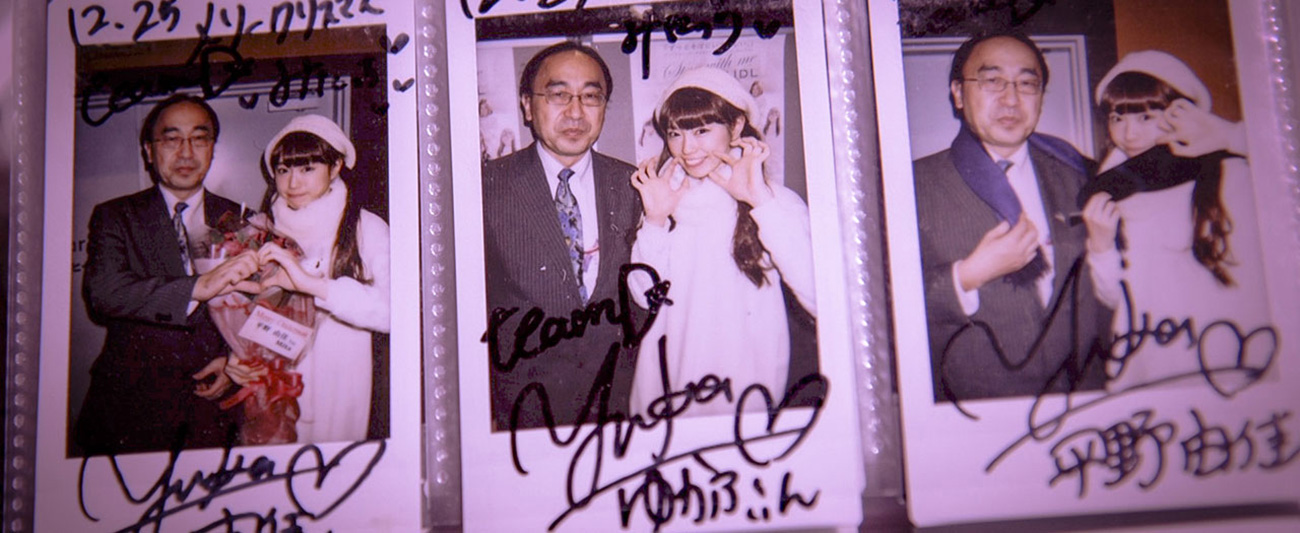

Koji Yoshida is one of the informal leaders of Rio’s fan club, who call themselves the RioRio Brothers. Koji describes himself and other male idol fans as ‘otaku’, the term used in Japan for extreme pop culture fanatics, whose behaviour is often characterised by giving over their whole lives in support of their passion. Indeed, Koji admits that he spends thousands of dollars a year on idol concerts, merchandise, and meet-and-greet sessions with performers, and that he is more comfortable with the idea of a fan relationship with an idol than a romantic one with an ordinary woman.

The film does indeed highlight the challenging nature of how idols are femininely coded primarily as young, innocent and pure, and how this plays into cultural stereotypes within Japan as to the ideal form of female desirability. While a few of the male fans display some awareness as to how their obsession with idols prevents them in many ways from having healthy ideas of women, most are oblivious to the troubling aspects of their behaviour. Some outright admit that romantic relationships are simply too much work, and the kind of bond formed with an idol – where attention is given without any effort beyond money on behalf of the fan – is far more desirable.

This transactionable relationship between fans and idols allows for some deeply disturbing behaviour to develop and flourish. Sequences later in the film that reveal that the pop idol phenomenon stretches to performers who are literally children, and still attract fawning men who are clearly delighted at this culturally sanctioned means of indulging in paedophilic expression, are gut-churning. There is an argument to be had that Miyake could have explored this aspect further in more explicit means, but personally what was shown said more than enough.

For director Miyake, working on this project was a means of confronting everything that made her uncomfortable about womanhood in Japan, as embodied by the idols. During a Q&A at a screening of the film at the Sundance Film Festival in January earlier this year, Miyake told of how when she was growing up every time she behaved in a way that wasn’t deemed ‘cute’, it was viewed as defiance by those around her. This resulted in her deciding to spend most of her young adulthood outside of Japan. The idols for her represent how constraining and limited the concept of ideal womanhood is to attain, and is framed through what men desire, not women.

Yet Miyake also had her preconceptions of women who are idols challenged by Rio. Unlike the fame-obsessed girls blindsided by their own internalised misogyny that Miyake expected to find, Rio is a resolutely sensible and canny businesswoman, who intelligently understands the hard work required to succeed, and the many downsides of the idol industry. Indeed, Rio never intended to be an idol, and avoids marketing herself explicitly as one. “I see this as a training ground,” she states early in the film. “My real dream is to be a singer.” Rio is not a person fooled by glamour; she is an artist and entrepreneur firmly in charge of her own agency and image, and knows how to play the game to get to where she wants to be.

The film is constantly traversing the grey areas thrown up by the idol industry, especially via the players Miyake focuses on within it. Rio is a product to be sold within an exploitative industry, yes, but her music constantly expresses ideas of headstrong womanhood and community that inspire her fan base in surprising ways. Koji says that what he finds so compelling about Rio is her tenacity in achieving her dream. As a salaryman, Koji looks upon his life’s choices with regret. “It’s been an easy, mediocre life. Totally devoid of excitement.” Rio fills a motivational emptiness in his life that provides him with guidance, to live with more passion and meaning: “I always look up to her.” Their relationship is a strange, complicated binary of star/fan, product/consumer, mentor/student, little sister/big brother, daughter/father and any number of other dichotomies, and each benefits yet feeds off of each other. It’s to the film’s credit that it doesn’t attempt to simplify these complications into basic good or bad categories – all the messiness is thrown up for us the viewers to wade through, and make our own conclusions.

As fan cultures become more prominent in the mainstream (or, indeed, become the mainstream itself), it’s pertinent to have films like Tokyo Idols which examines what happens when our passions become channelled into properties and people that demand our cash to survive. And when our love for movies, music, comics and the people who create them overwhelm our ability to emotionally connect with the people that surround us we need to put these issues into perspective. The problems of idol and otaku culture may seem extreme or lazily written off as a peculiarly Japanese problem. But anywhere where there are pop culture conventions, online fan communities, platforms like Twitter and Instagram where we can see into our own personal idols’ lives, and they can reflect what we want from them back at us, there’s the potential for a fan to feel more comfortable with the perception that their idea of a famous person is better than real connection — no matter the cost.