For many of us, our teenage years are a period we hope to never relive. If a time machine is invented, I know exactly which stop I won’t be making. But every time I watch a film by Japanese director Shunji Iwai, I find myself transported backwards to a time when life was a topsy-turvy adventure and I was holding on by the skin of my teeth.

Iwai has amassed a devoted following because of his ability to transform the loneliest period of one’s life into lyrical poetry, and his films are beloved by those who see themselves in his characters. He can recreate the anxiety, fear and instability of those years like almost no one else can, while crafting his stories with an illusory quality that makes us question how much we truly know about his characters and their world. With a series of signature techniques, Iwai keeps his audience off-kilter and uncomfortable to evoke the dizzying feeling of this epoch in one’s life.

Are you ready to take a trip back in time?

“Don’t you think real people are scarier… than zombies and ghosts?

When you’re growing up, it feels like the rules are always changing. Expectations keep rising, responsibilities are piling up and you’re constantly questioning yourself. “Who am I? Is who I am good enough? Do my friends even like me? Will anyone ever love me?”

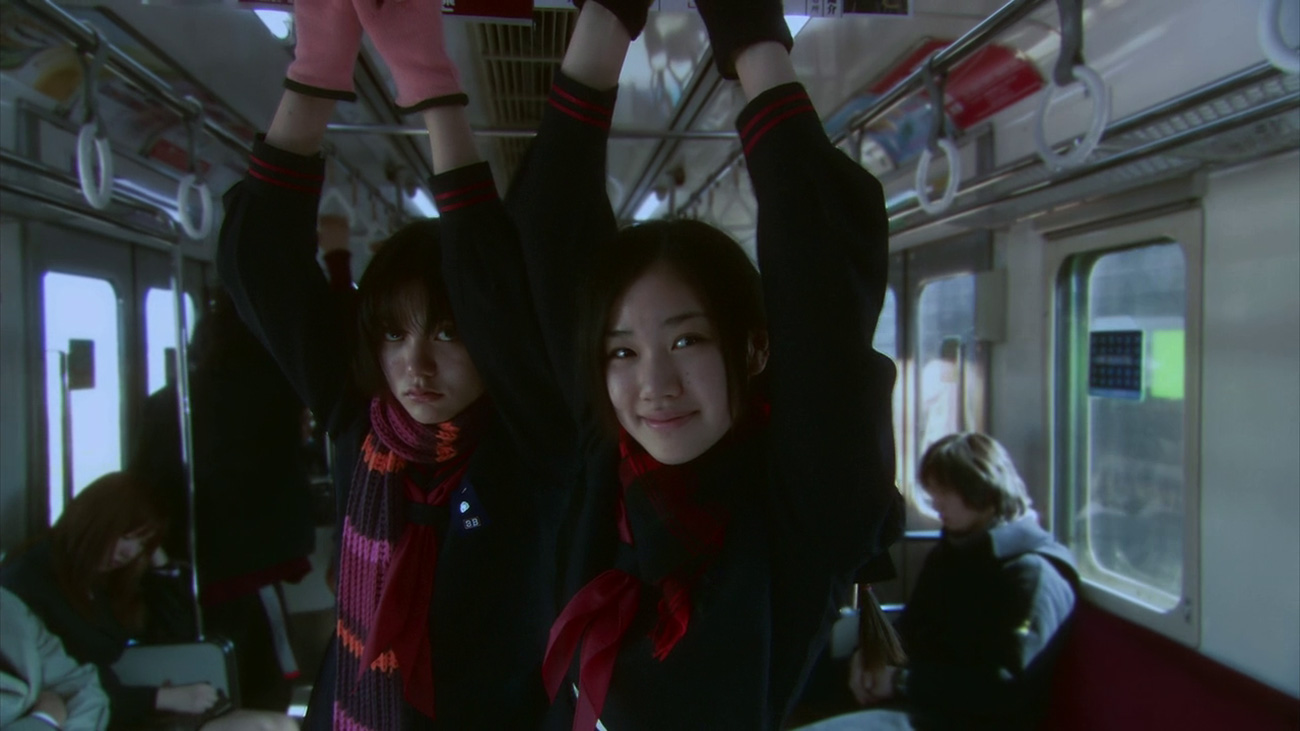

In Iwai’s Hana and Alice, middle schooler Hana cons her crush, Masashi, into believing he got amnesia after bumping his head and she is the girlfriend he can’t remember. Her best friend, Alice, plays along by pretending to be Masashi’s jilted ex-girlfriend. Together, they ensnare Masashi in a web of lies and make him feel guilty for treating them badly during an ordeal they invented.

While the girls toy with Masashi’s sense of reality, Iwai toys with our understanding of their motives. Hana and Alice are performers; they both attend ballet class and Alice goes on acting auditions on the weekends. And when they’re with Masashi, they’re still performing. It’s all happening for someone’s entertainment; ours and theirs. Through their lies, they create a whole different reality. Lies have a tendency to do that. The longer we maintain a lie and build upon one lie with another, the harder it becomes to dig ourselves out and even remember what the truth was. It’s no wonder Alice begins to fall for Masashi and morphs exactly into the girl she was pretending to be. Masashi falls for her too, further complicating his relationship with Hana.

By the movie’s end, Masashi has discovered the truth and shunned both Hana and Alice. But they hardly seem scarred by the incident. In the final scene, Hana is teasing Alice over a modelling shoot and they seem to have moved on entirely. Is it just because middle schoolers are fickle or was their love for Masashi just for show? After all, what better way to recreate the thrill of watching a romantic drama, than to contort your life into one?

The plot reads like a comical romp, and maybe another director would’ve treated it as exactly that. We would’ve seen the girls as silly rather than cruel, and Masashi’s ordeal as hysterical rather than tragic. But Iwai takes a more straightforward approach, and treats his characters with respect and not like foolish children. He builds their world, puts his camera in the center, and observes. They’re allowed to wander along their misadventures, without an adult providing advice and trying to nudge them onto the right path. Iwai won’t judge or absolve them either. That’s what makes his films transformative and compelling, regardless of what age you are when you watch them.

“Kids these days are very scary.”

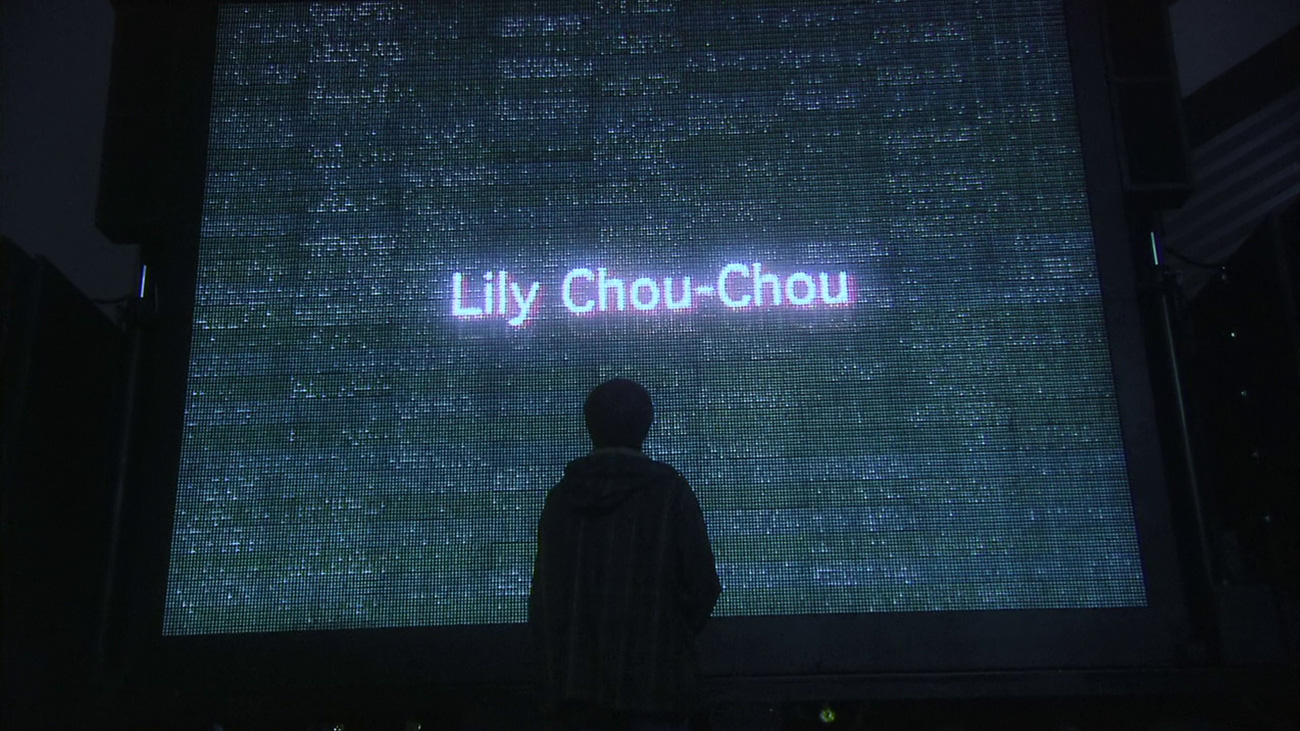

You can love it or hate it, but you definitely won’t forget it. Iwai’s All About Lily Chou-Chou mystified some audiences and became an inedible touchstone for others. Prostitution by blackmail and vicious bullying punctuate a story about a bunch of alienated teens stifled by the rigor of school and familial expectations. The title references one of the film’s characters, an elusive popstar who is the fixation of the protagonist, Hasumi.

Tense and claustrophobic, this film captures the post-Y2K generation, who have just figured out the world is not ending and they’ve got a whole life left to live. Throughout the film, you see teens with their heads in books, music flowing from their headphones and their eyes glued to screens. Anything to distract from life and subtract the time left. But these distractions are just temporary fixes, because as soon as they lift their heads, Iwai pushes them back into the frenzy of ‘real life’.

We are watching a generation who has grown up with technology so their understanding of the world is not limited only to what is tangible. Reality is no longer what we experience in front of us, but also inside the infinite darkness of the internet. Online conversations take over the entire screen at certain points in the film, making it seem as if we are the ones on a computer, typing back and forth with strangers. We see two usernames conversing with each other, but we don’t know which characters in the films are using which username until the very end. A title card with “reload” written on it flashes on screen sometimes, along with other text taken from online conversations. All of these techniques ask the audience to question reality, not only within the film, but within our experience of watching it. Do we know what we’re seeing and do these teens understand it either? They have no idea who is on the other side of the screen, they can only take people at their word. Indeed, the film’s biggest reveal is exactly who is behind these usernames and it’s a subversion of our expectations.

Iwai brought on board music composer and keyboardist Takeshi Kobayashi and singer Salyu to create the music of Lily Chou-Chou. This adds another layer of (un)reality to the film. Technically, Lily Chou-Chou does not exist as a performer but she also does, because music was created under her name and it’s available to listen to even now (thank you, internet). This is kind of like Iwai’s take on a John Hughes film. The music in Hughes’ movies are so iconic, but it was the music that the cool kids danced to at parties. It wasn’t the music that they turned up loud when they wanted to drown out the sound of their parents fighting. Lily Chou-Chou’s music is melancholic and grungy, imitating the sound of popular ‘90s Seattle bands. But there’s also a post-modern element to it, mostly levied by Salyu’s voice, which sounds like audio captured from space. Or, from the ether rather.

All About in Lily Chou-Chou is, in a way, the best representation of Iwai as an artist who has a strong grasp on how to use music in films. To this day, he moonlights as a music video director and has cast pop stars in his movies. With music, Iwai brings us into his characters’ psyche and adds colour to their world. He also has a strong understanding of how to meld music and images to evoke powerful emotions. In his films, we can really hear the music; the scenes they play underneath do not overpower the music, but bring it to the surface.

Similar to Hana and Alice, but taken a step further, it feels Iwai has handed the reins over to the will of his characters. In some of the film’s most tense moments, the screen is overtaken by a camera being filmed by the teenagers. It is as if Iwai is seceding his directorial vision to them. This is just another way Iwai effectively brings the audience into their world. He is saying: “This is their story, not mine. So just watch.”

“Miracle of love.”

You’d think the hard part is over when high school ends, but Iwai would say you’re wrong. Many films that take on college life, particularly out of America, portray it as a time filled with sexual promiscuity and dabbling with narcotics. But April Story hones in on a theme not explored as often: loneliness.

The protagonist, Uzuki, moves away from home to attend university in Tokyo. After failing to make friends at school and in her neighbourhood, she falls into a mundane routine. She revisits the same bookstore, bicycles around the city, eats dinner alone and escapes leering perverts in movie theatres.

The opening scenes of Iwai’s films commonly provide a glimpse into the protagonist’s state of mind or their familiar habits. There’s no mystery about whose story we will be following as they appear on screen almost immediately. However, in April Story, the first shot is from the protagonist’s visual perspective, facing her family as she bids them farewell. And it’s the perfect way to introduce this character as it shows us she is eager to make her family proud and focuses on their emotions during her departure, rather than her own fears. Later on in the film, we will watch her continue to cast aside her own comfort to appease others. Like the characters in All About Lily Chou-Chou, she also wastes away time with books, movies and music; the noise she needs to suffocate the quiet.

Iwai doesn’t seem to play much with reality here, until we realise the story we were watching isn’t at all what we assumed it to be. With some flashback sequences, we discover Uzuki came to Tokyo to be close to her high school love, who also moved to the city after graduation. This shy girl, who seemed to be overwhelmed by her new life, actually arrived in Tokyo with a well-defined purpose. With this new piece of information, Iwai forces us to discard our previous notions and rediscover the film with a fresh pair of eyes.

We’re then pulled from a quite naturalistic film and plunged into one that dazzles with magic. In the last scene, Uzuki is caught in a terrible rainstorm and finds shelter under a red umbrella that doesn’t belong to her. But she’s smiling because she’s just reconnected with her love. She reflects on how her homeroom teacher said it was a “miracle” she was accepted into the Tokyo university she now attends. It was a “miracle of love”, she thinks. As she stands in the storm, it seems like the rain doesn’t bother her at all.

“Of course, I do remember him.”

The release of Love Letter in 1995 was a breakthrough in Iwai’s previously modest career, becoming a domestic hit and receiving accolades abroad as well. The film follows a widow, Hiroko, who exchanges letters with a former classmate of her late husband. In the beginning, Hiroko believes these letters are coming from her husband, until she realizes he had the same name as a female classmate: Itsuki Fujii. During this penpal relationship, both women learn new things about this man, who they knew at only during particular periods of his life. As the classmate reminiscences, we’re shown flashbacks to their time at school and uncover a love story about a boy who was too shy to ever tell his crush how he felt.

Like Iwai’s other films, we are drawn into a story that plays fast and loose with reality. Iwai uses hazy flashbacks, dreamy cinematography, the same actress to play two characters and has two people share the same name. It’s not long before our heads are swirling as we try to follow their parallel narratives and understand how scenes about the past will define what happens in the future.

Singer and actress Miho Nakayama plays both female characters, even in the same haircut. But there is a marked different between the two characters; the demure Hiroko who is desperate for any information on her late husband’s past, and excitable Itsuki, who spends most of the movie fighting off an illness and refusing to see a doctor. As we are sent backwards, we see more similarities between the character of Hiroko and young Itsuki, both bashful and unable to clearly express their wants. We can suppose male Itsuki married Hiroko because she resembled young, female Itsuki both physically and personality-wise.

Iwai has said: “My creativity has been greatly informed by my early childhood, as well as my adolescence. And although I’ve grown up and become an adult, there has always been a part of me that identifies with those vivid memories of my youth.”

Therein lies the beauty, and subsequent success, of this film. The story itself is lovely, but Iwai’s fantasy-driven approach adds greater texture to the tale to really draw out our own sweet memories of youthful love. The opening scene sees Hiroko lying in the snow and letting snowflakes fall across her hair. Snowflakes melt upon touch, their beauty hardly savoured before they’re gone, just the way we can barely appreciate our first love before the moment has passed and we’re left only with our memories.

As it shifts between the past and the present, Love Letter shows the long-term consequences of decisions we make as teenagers. Perhaps, if this boy told his crush how he felt, it would have changed the trajectory of his life. He may have married a different woman and still be alive. The film raises these questions in the same way we look back on our past and wonder, “What if I had done this, instead of that? How different would my life be now?”

“The here and the now.”

Iwai has collaborated several times with the same cinematographer, Noboru Shinoda, and it’s remarkable to know this pair made all the aforementioned films. They each look rather different from one another, but manage to retain the same lyricism. Iwai and Shinoda allow the story to be their guide when they define the visual makeup, instead of imposing their preferred aesthetic on the story. This choice enhances the individual themes and characters, and allows the audience to be enveloped by the narrative. We breathe alongside them, we experience their world as they experience it and we understand the complexities of their emotions. Iwai brings us in; he doesn’t allow us to sit passively in our seats and watch.

Often, teenagers’ stories are disregarded and treated as lesser than. What do a bunch of kids know about real problems? Sure, teenagers certainly haven’t seen it all yet, but what they do see, they’re often unable to process and it leaves a mark on their psyche. The discoveries we make and insecurities we develop as teenagers, we can carry with us for decades, if not forever. But why watch these films? Why be reminded of vicious teens, awkward bodies and unrequited loves? Because to look backwards is to see how much we’ve grown and to remember, we’re alive now and there’s still so much more of life left to see.

Or as Iwai put it: “As children, we experience time and reality uncompressed, and in HD. But the older and more world-weary we get, the more compressed it all becomes. We convince ourselves that tomorrow will be no different from today. Life increasingly becomes a blur. And then one day we find ourselves asking where our lives went… it’s so important that we hold on to that wide-eyed wonder we had as children. We have to really savor the time that we do have. The here and the now.”