What is it about Kiki’s Delivery Service — a film about a 13-year old witch who moves into a new phase of her life — that still resonates deeply with young women 30 years after its initial release?

Like the best films in Studio Ghibli’s oeuvre, the secret to Kiki’s Delivery Service is its simplicity. There are no antagonists, no lofty quests and no kingdom to save. It also isn’t bogged down by plot or exposition.

Instead, this beautiful film is content to let its characters breathe and live in a world created by its incomparable writer-director Hayao Miyazaki.

As Kiki’s Delivery Service turns 30 this year, we reflect on Studio Ghibli’s first financial success at the Japanese box office by sharing the stories of young women from around the world who’ve been touched by Kiki’s coming-of-age journey and who now, as adults, find themselves relating to her story more than ever.

A journey of self-discovery

“In an era when leaving the security of one’s home is no longer anything special, and living among strangers means nothing more than going to a convenience store for anything you need, it might be more difficult than ever to achieve a real sense of independence since you must go through the process of discovering your own talents and expressing yourself.” – Hayao Miyazaki, foreword of The Art of Kiki’s Delivery Service

Stories about young women have often focused on a limited idea of what it means to be strong and empowered as a woman. They often focus on an obvious physical and mental strength that lacks room to explore vulnerability or weakness. Kiki’s Delivery Service subverts this by showing how a personal journey can only be made richer by allowing yourself to fall and to reach out to others. Furthermore, Miyazaki characterised Kiki as a witch who strove to be self-reliant and independent yet also allowed her to express her insecurities and vulnerability.

It’s these story and character qualities that have allowed many young women to identify in Kiki’s journey like Singaporean native Christal, 26, who has lived in New York for the past seven years and currently sees herself connected to Kiki’s growing pains.

She recounts: “When I first watched Kiki’s Delivery Service I was still in the comfortable bubble of school and living at home, where nobody really gave me a hard time and I was still dreaming about what life as an adult could be. Right now I’m living it and people give you a hard time in real life. Also the money struggles are real!”

Vicky, 26, from Washington DC notes the film’s honest depiction of growth–and how support from older mentors is important to the process–as a trait that has helped the film remain relevant to the experiences of young people.

“[Kiki’s] experience of striking out on her own and trying, perhaps foolishly, to do it all on her own is extremely relatable. But you can sense the relief she feels every time she allows herself to take advice, and it only ever helps her move forward. [Kiki’s Delivery Service] is a great story about learning from your mistakes that are harder to define, because they’re only mistakes in how you treat yourself, not mistakes that affect others directly.”

Eva, a 27-year old from Hong Kong supports Vicky’s sentiments and further adds: “I think while there are things we need to tackle and overcome by ourselves, it is also nice to know that your struggles are also faced by others and the advice they give you is rooted from their own experience and that you are not alone in the world.”

Meanwhile, Mel, a 23-year old writer from Tunisia, points towards the film’s lack of romance as a major reason why she feels Kiki’s journey sets the character apart from other Studio Ghibli heroines and a majority of other coming-of-age films.

“I love that the film focuses on Kiki’s journey to find herself, to mature as not only a witch but also a person,” Mel says.

As valuable as love and romance are, Studio Ghibli’s films have always shown that the greatest journey and relationship is the one you have with yourself.

Vulnerability, loneliness and isolation in growing up

“Kiki is protected by mother’s old but well-looked-after broom, she has the radio that was a gift from father, and the black cat she is so close to that it is almost like a part of herself, but Kiki’s heart wavers between isolation and longing for human company.” – Hayao Miyazaki, foreword to The Art of Kiki’s Delivery Service

In learning to be happy with herself, Miyazaki also presented a multifaceted look at what it means to be vulnerable and alone as a young person striking it out on their own for the first time with his film.

Loneliness is complex. There’s the loneliness you feel without anyone to connect with. But there’s also the gnawing emptiness that comes when you feel emotionally disconnected and alone, even with friends.

In a key scene that perfectly summarises millennial ennui, Kiki returns to her room after a social situation and slumps face first into the bed, muttering, “I think there’s something wrong with me, Jiji. I meet a lot of people and at first everything seems to be going okay. But then I start feeling like such an outsider.”

Claire, who is 24 and currently based in London, cites the above as one of her favourite scenes because she sees it as a symptom of knowing when to step back and take a break.

As someone who moved from a small town in Western France all the way to the bustling heart of London, she says, “I decided to move away to a big city where life is very fast paced and the city gets very lonely. I come from a small town and although I knew that living in a big city would be different, it still gets very hard. Sometimes I’m afraid I’m losing myself in all the hurry.”

Jennifer, 27 from Caracas, Venezuela, also sees herself in Kiki’s loneliness and further cites political dissent in her country as a compounding factor.

“My country is going through a rough situation and a lot of young people have immigrated, including many of my friends, so it’s something I’m struggling with. It’s not that easy making friends as an adult,” she says. Finding and nurturing a meaningful connection as an adult can be tricky. Without that kind of emotional support, it is easy to become lonely.

This loneliness is also illustrated in Kiki’s relationship with her feline companion, Jiji. Although Kiki is initially confident in her abilities and place in the world, doubt eventually creeps in and wavers her resilience. This worsens to the point where Kiki loses the ability to talk to Jiji, thus alienating her from her lifelong pet and confidante. Even when Kiki gains back her ability to fly, she is no longer able to talk to Jiji.

For Lauren, 25, from Hawaii, she felt this narrative choice signalled that “Jiji was a physical manifestation of Kiki’s doubts and worries”.

“It is a scary thing to be secure within yourself and to trust your own decisions. Kiki having to let go of that communication with Jiji didn’t necessarily mean she didn’t have those feelings anymore, because Jiji was still her companion, but that she had fully given herself permission to make mistakes,” Lauren says.

Christal has a slightly different take and recognises “that in growing up, naturally there will be a loss”. Jiji, who is mistaken as a stuffed toy at one point in the film, can come to represent a symbol of childhood that gets left behind in Kiki’s own transition to adulthood.

Work, work, work, work work

Kiki’s Delivery Service may take place in a picturesque fantasy town, but its portrayal of career satisfaction in young people hits closer to reality. In the film, witches are established as having one skill that they hone and contribute to the town they make their home. Kiki’s mother’s skill is potion-making. The young snobby witch she meets on her first night out has her fortune telling. For Kiki, her chosen pursuit is flying, which she is initially confident in.

But like many young people entering the working world, Kiki soon realises that she’s no longer a big fish in a small pond.

“[Kiki’s] self-doubt is something that gets to me every time I see the film. Am I actually good at this thing I dreamed of doing for so long? What else can I do then? This feeling can easily creep in and taint everything in your head,” Jennifer says.

This is most evident in Kiki’s loss of her magic, something that hits close to home for Mel who likens Kiki’s experience in the film to that of her own writer’s block. “I see myself in Kiki when she loses her magic,” Mel says.

Keeping that drive to be productive is no doubt challenging, particularly when it is compounded by a need to use what you’re good at – in Kiki’s case, her proficiency with flying – to earn your keep. In what could only be described as Kiki’s own version of burnout, Jennifer, who is working in a role she would hesitate to call her dream job, relates: “I can definitely understand how feeling stuck in a routine can kill all motivation”.

Iman, a 21-year old from Sweden, said what struck her the most about watching Kiki’s Delivery Service as an adult was its depiction of burnout which she had rarely, if ever, seen portrayed on screen with younger people.

“I rewatched the film when I myself was burned out and had just dropped out of university. I felt like life was suddenly really difficult. Even simple things like buying groceries and seeing my friends would tire me and give me awful headaches. I almost didn’t feel like myself anymore. But rewatching Kiki and seeing her go through the difficulties of being a young adult, burn out and then at the end of the day still manage to recover and fly again was very comforting to me.”

The importance of female friendships and relationships

Many of the young women we spoke to felt Kiki’s attempts to connect with people was instantly recognisable.

Vicky loved how the awkward uncertainty of expressing oneself and meeting new people was portrayed. “As someone who moved around a lot growing up, it always struck me as being written directly about my experiences,” she said.

Similarly, Iman found the awkward experience of finding new friends in a new place the most relatable aspect of Kiki’s struggles. “I think everyone who’s ever moved to a new city where they don’t know anyone can relate.”

As the only witch in town, it was only natural for Kiki to have found it hard to relate to her peers. One of Kiki’s Delivery Service’s strongest aspects is therefore its establishment of Kiki’s relationships with older women.

Jennifer believes female relationships and friendships are often overlooked or oversimplified by male filmmakers. Kiki’s Delivery Service proves to be the exception. Nearly all the supporting characters in Miyazaki’s film are female and most of Kiki’s relationships are between women, even those who’re in the background.

“There are a number of women of different ages and different stages in their lives supporting Kiki,” says Lauren. “It was nice to see more than one depiction of what being a woman is and can be.”

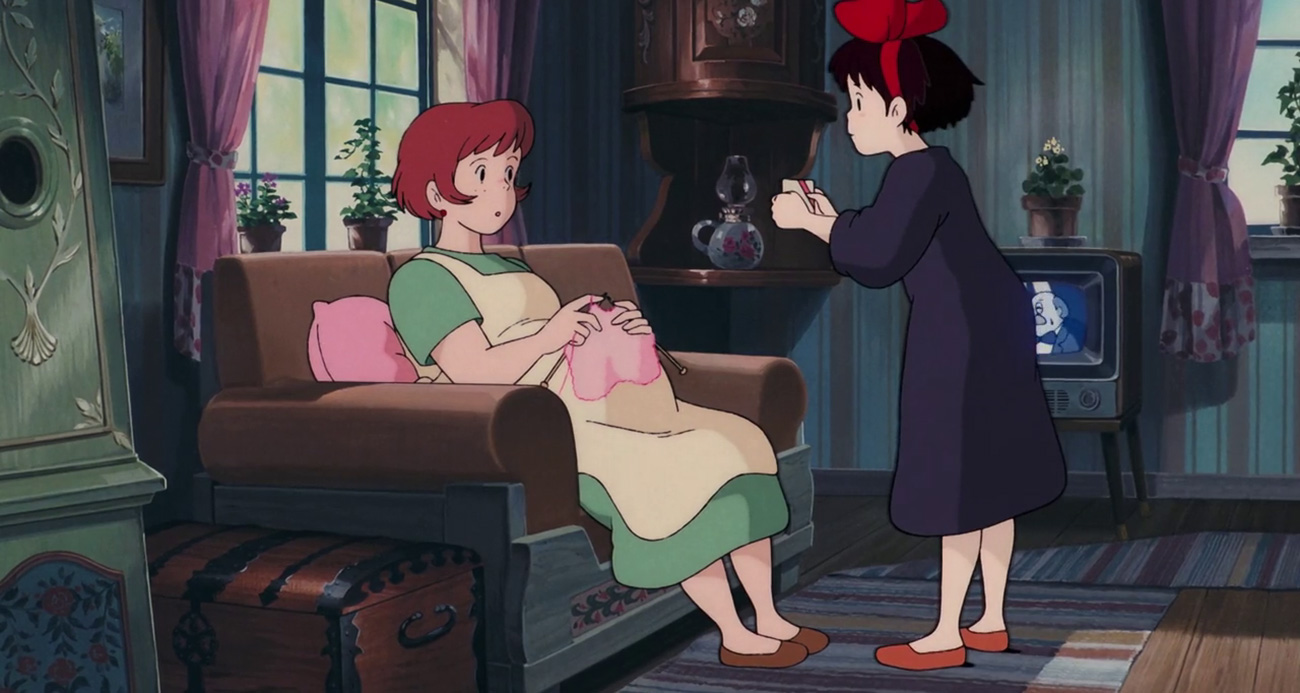

The two significant older women in Kiki’s new life are Osono, the pregnant bakery owner who gives Kiki a room and space to conduct her business, and Ursula, the free-spirited forest dwelling artist.

“In Osono she found a familiar maternal figure to lean on both materially and emotionally, but what Ursula was able to share with her was different since she was closer to Kiki’s age and was also in the process of her own pursuit,” says Christal.

Lauren explains that these characters are important in showing young girls that they have true allies in their lives.

“[Osono] consistently demonstrates her love for Kiki and offers her a place to put down roots. Ursula is wonderful because she helps Kiki process her emotions and presents vulnerability in a way that makes Kiki feel safe,” Lauren says.

“[It] validates that her emotional slump is not only normal, but necessary. These two women never infantilize Kiki or her issues. They let her sort through her ordeals and take the lead when they know it’s needed.”

Almost everyone we spoke to cited Ursula as their favourite supporting character. Ursula represents so many things to Kiki. She is a friend, a role model, an inspiration, but she is never placed on a pedestal.

On Ursula’s importance to Kiki, Jennifer says, “[Ursula is] someone Kiki can be close with and offers guidance without judgement. It’s important that she lets Kiki know everyone has slumps and moments where they feel everything is ending but you can push through and her worth isn’t tied to her work.”

One of Claire’s favourite lines is delivered by Ursula who in the film says to Kiki, “We need to find our own inspiration, and sometimes it’s not easy”. For Claire, when she hears Ursula re-assure Kiki like this, she thinks of the many young women, non-binary people and young people in the LGBT+ community she has met since moving to the big city.

“I’ve come to learn so many things through them, grow my interests and find my inspiration.”

30 Years Later…

“Dear mother and father. How are you doing? Jiji and I are fine. Everything at work seems to be falling into place nicely. I’m even starting to gain some confidence. There are still times when I feel sad…but all in all, I sure love this town.”

For Christal, rewatching Kiki’s Delivery Service now as an adult is to see her life reflected before her. She reminisces about college, life as a graduate and the growing pains of establishing her life as a working adult. The biggest takeaway for her reflecting on the film?

“Eventually you have to realise your value should come from within, but it’s hard to remember all the time,” she says.

And that’s okay. It’s okay to not have everything figured out and to doubt yourself, and to struggle. The final lines of the film where Kiki writes to her parents saying, “There are still times when I feel sad…” is particularly poignant because in a lesser film, everything about Kiki’s insecurities would be wrapped up in a neat bow.

Kiki’s Delivery Service is a reminder that life isn’t ‘life’ if you are not allowing yourself to feel everything it is you feel. The imperfection of her journey is what makes the story compelling and universal. “It’s not an arc with a particularly low point and then a splashy redemptive moment,” elaborates Christal on the nuances of that ending and how Kiki’s journey of self-discovery appealed to her.

There are so many more reasons why Kiki’s Delivery Service has continued to stand the test of time. But perhaps its staying power with young women in particular can be best summed up by Jennifer: “Miyazaki portrays young women with compassion that many people in real life don’t often give us.” There’s a deep empathy in the film that finds value in the ordinary and validates the experiences of young women everywhere. And with its reassuring touch of magic, Miyazaki’s tale of this little witch will no doubt continue to touch the lives of young women for years to come. If there is one film that you need to watch before you leave home for the first time, start a new job or a new life, make Kiki’s Delivery Service that film.

This feature is accompanied by original artwork produced by Singaporean artist Lesley Tang. For more of Lesley’s work, follow her on Instagram (@yelselogy) and check out her official website.