Japanese filmmaker Juzo Itami was fearless. His films skipped past the ordinary, headed straight for the whimsical, and satirised Japanese society with lighthearted wit and idiosyncratic style. The success of his ramen Western, Tampopo (1985) had domestic and international audiences fawning over the most exciting Japanese director since Akira Kurosawa. Tampopo remains his most well-known film, but another Itami film has had a more fascinating legacy.

At the time of its 1992 release, Minbo no onna: the Gentle Art of Japanese Extortion was hailed as the most realistic depiction of Japanese crime and corruption. Japan’s notorious gangsters, the yakuza, were portrayed as blubbering villains and the film provided the public with a manual for defeating them. Itami’s cinematic confrontation of the yakuza may have cost him his life, but he was guided by the words his father scrawled into the margins of a script: “To offer people comfort must be the noblest role possible for cinema.”

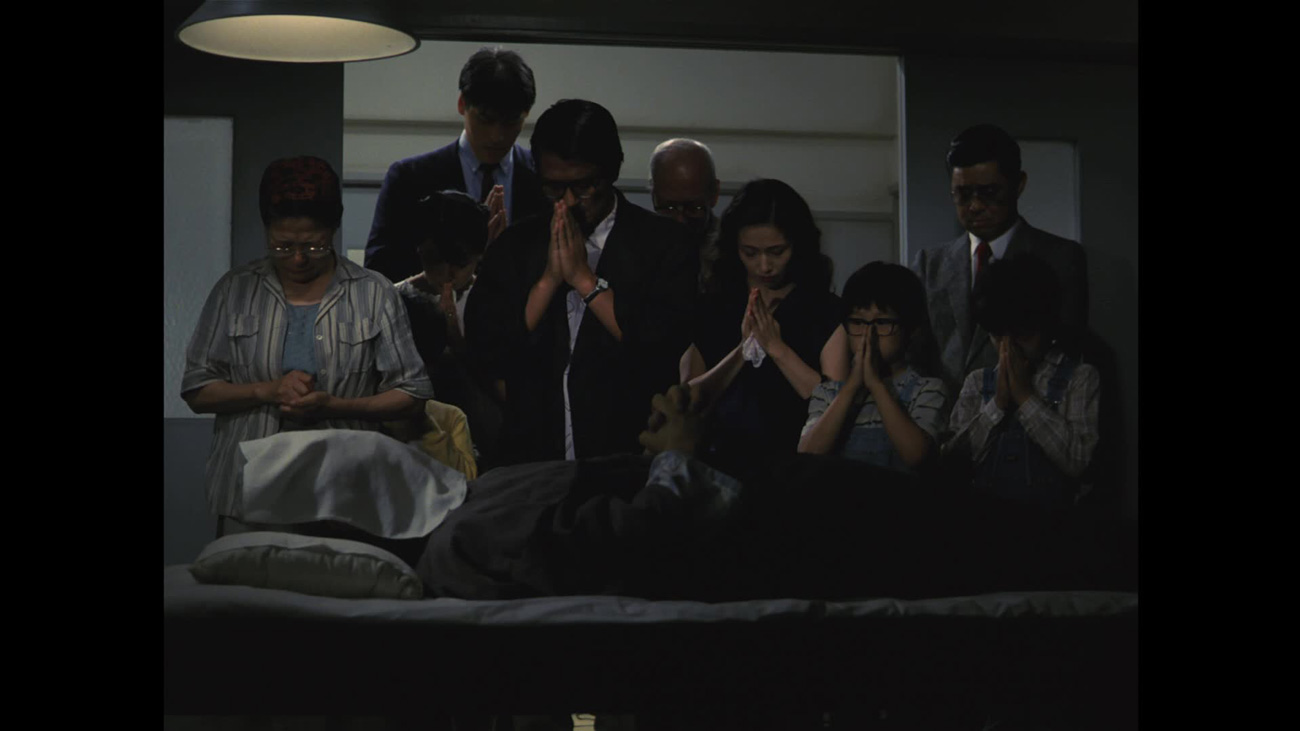

The End is the Beginning is the End

From Juzo Itami’s debut film as a director, ‘The Funeral’ (1984).

Juzo Itami’s father, Mansaku Itami, was a prominent writer and director of satirical films. Itami himself wouldn’t step behind the camera until the age of 50, working first as an actor, TV host, essayist, amateur boxer, translator of American novels, and graphic designer.

“The movies were my father’s business. It was too high a mountain for me to climb,” said Juzo Itami in a 1993 interview. “But after raising two sons and reaching the apex my father did when he died, I felt I could climb the mountain.”

Mansaku Itami’s death in 1946 from tuberculosis left an indelible impression on his young son. Itami made his directorial debut in 1984 with The Funeral, depicting the family politics behind funeral preparations. It was a box office success and won five Japanese Academy Awards, Japan’s equivalent of the Oscars, including Best Film and Best Director. Itami was quickly crowned the new star of Japanese cinema.

The 1980s marked a turning point for the yakuza too. For decades, they operated along the fringes of society, hidden away in shadowy gambling dens. When Japan experienced an economic boom, the yakuza wanted in on the action. They played the stock market, made bets on real estate, and profited to the tune of billions. They infiltrated company boardrooms and politicians’ offices, and swatted policemen away with wads of cash. They poisoned every aspect of daily life, bringing their gang wars to the streets with innocent people caught in the crossfire. The Japanese public grew furious – requests for police help doubled against gangs from 1981 to 1991, and public demonstrations and lawsuits targeting the yakuza became common.

While the yakuza were raking in money, so was Juzo Itami. The success of The Funeral had pushed him into a higher tax bracket and he was hit with a tax bill in the range of 250 million yen ($2.25 million USD). This experience inspired him to create The Taxing Woman (1987) and The Return of the Taxing Woman (1988), both of which follow a relentless tax auditor played by his wife, Nobuko Miyamoto, who starred in all his films. The films examined the process of tax collection in Japan and the fixation on making it rich that seized the Japanese public during the economic boom.

In 1991, the boom went bust and a string of financial scandals involving the yakuza came to light. Itami’s observations of his country’s economic upheaval were channelled into Minbo no onna, where he took direct aim at skewering the yakuza.

The Gentle Art of Yakuza Humiliation

‘Minbo no onna’ (1992) made a mockery of the yakuza and garnered the wrong kind of attention for Itami.

Minbo no onna is set inside a hotel infested with yakuza cutting deals and being a general nuisance. The hotel owner is desperate to win a lucrative contract to host a summit between international officials and makes several failed attempts to push the yakuza out. Here, the film’s hero sashays onto the screen; a hard-boiled lawyer played by Nobuko Miyamoto. Miyamoto’s character calls the yakuza out on their bluffs and uses legal maneuvers to upend their dirty tricks. The frantic and episodic nature of the film recalls the way yakuza were handled in real life; a citizen calls the police, the yakuza get a slap on the wrist, and the next day they’re back in business. Rinse and repeat. When the yakuza would spit out threats, Itami let their faces dominate the frame. But the more Miyamoto’s character pushed back, shattering the yakuza’s plans beneath her heels, the further the camera pulled away.

Previous Japanese films romanticised the yakuza with melodramatic tales depicting them as Robin Hood-like figures and the yakuza’s self-mythologised image was of modern-day samurais. In Minbo no onna, they are foolish extortionists who make working-class people miserable. What offended the yakuza most was the film’s claim they never followed through on their threats. For the sake of their reputation, they couldn’t let the Japanese public believe that.

After Minbo no onna’s theatrical release, policeman began patrolling Itami’s Tokyo home every half an hour and advised him on what to do if he was attacked. They were anticipating retaliatory actions but Itami was telling the press, “I don’t think anything will happen.”

One week after the film’s opening, Itami was assaulted outside his home by several young men brandishing knives. They sliced two-inch deep wounds into his face, neck, and arms.

“They cut very slowly. They took their time,” said Itami afterwards. “They could have killed me if they wanted to.” He managed to get away and the men escaped into a black car. Itami entered his house, dripping with blood, and told his panicked wife to call an ambulance.

During an eight-day hospital stay, Itami wrote a letter addressed to the public: “Yakuza must not be allowed to deprive us of our freedom through violence and intimidation, and this is the message of my movie. What worries me most about this incident is that people might think that the yakuza really are scary. It would be a shame if people were disheartened just when the public is beginning to stand up against organised crime.”

Japanese police arrested the men involved with Itami’s attack, but they would not confess who ordered it. They each received prison sentences ranging from four to five years.

After leaving the hospital, Itami returned to promoting Minbo no onna. With a freshly scarred face, Itami would show reporters a photograph of his wounds taken shortly after the assault. He felt vindicated, saying, “The fact that I was attacked proves that what I pointed out in my film was correct. If I was wrong, they wouldn’t have reacted so strongly. I pointed out the truth, and they wanted to stop this information from spreading”. Itami became a symbol of a modern Japan that no longer accepted the yakuza as an unmovable part of society.

Five years later and four films after Minbo no onna, it was rumored Itami’s next film was about the suspicious relationship between Goto-gumi, an affiliate of the biggest yakuza gang, and Soka Gakkai, a Japanese religious organisation that boasted 12 million members worldwide. The yakuza allegedly caught wind of Itami’s plans and were determined to stop him.

An Honorable Death?

Yuzo Itami with wife and actress Nobuko Miyamoto.

In late 1997, a Japanese tabloid, Flash Magazine, was preparing a story that alleged 64-year-old Itami was having an affair with a 26-year-old woman. They had black-and-white photos showing Itami and the woman walking down the street and dining at a French restaurant. They would quote the woman as telling friends Itami enjoyed “unusual sex games” and had given her a large sum of money. The magazine called Itami, giving him a heads-up about the article and offered to tell his side. Itami calmly explained having interviewed the woman in connection with a film he was making about office workers. He admitted to giving her a loan, but it was to help her with the costs of moving.

On December 20, 1997, two days before the article’s scheduled release, Itami leaped to his death from his condominium office. A suicide note printed from his computer and placed on his desk read, “My death is the only way to prove my innocence. I cannot find any other means to prove that there was nothing.” A picture of Nobuko Miyamoto was left on the computer screen and in his note, he referred to her as “the best wife, mother and actress in Japan”.

His family was shocked and his friends were suspicious. Itami satirised Japanese traditions, yet committing suicide to preserve honour was authentically Japanese. The suicide note reeked of melodrama, which the director had always sneered at. Itami had also written an essay declaring affairs between men and women in Japan were natural, so why would he have been so ashamed of his? And why was the note printed from his computer rather than handwritten?

An alternative theory arose: the yakuza murdered Itami. The police investigated this angle but their final verdict was suicide. Itami did not want a funeral, so family members gathered to watch his films at a memorial service instead.

Decades later, Itami’s death is still branded with a big fat question mark. For his 2009 book, Tokyo Vice, journalist Jake Adelstein interviewed yakuza members who worked for Tadamasa Goto, the founder of Goto-gumi. It was rumored Goto was the one put the hit out on Itami. The crime boss wrote in his autobiography, “[Minbo no onna] was an unpleasant movie. It insults the yakuza, it ridicules us — but while I didn’t give the order, when I found out that one of my boys had gone out and slashed him up, I was proud of him.”

A former member of Goto-gumi told Adelstein that he was there the night Itami died, saying, “We set it up to stage his murder as a suicide. We dragged him up to the rooftop and put a gun in his face. We gave him a choice: jump and you might live or stay and we’ll blow your face off. He jumped. He didn’t live.”

While doing research for his book, Adelstein befriended a leading anti-organised crime lawyer, Igari Toshiro (who was found dead in 2010 with his wrists slashed while he was writing a book about the yakuza). Adelstein asked Toshiro why he continued his risky line of work. Toshiro explained, “[If] you capitulate, if you run away, you’ll be chased for the rest of your life. And if you’re being chased, eventually what is chasing you will catch up. Step back and you’re dead already. You can only stand your ground and pursue. Because that’s not only the right thing to do, that’s the only thing to do.”

Nobuko Miyamoto remained under police protection for twenty years after Itami’s death. Towards the end of Minbo no onna, her character recalls her father’s last words before his death at the hands of the yakuza: “Everybody dies sometime. And it’s better to die for your beliefs than live as a coward. Remember that always.”