Written for Japanese Film Festival 2017 in Australia. Filmed in Ether is a proud media partner of JFF 2017.

Take Quentin Tarantino’s pop-art stylings, Baz Luhrmann’s unhinged bravado, Nicolas Winding Refn’s neon fever dreams and Wong Kar-wai’s liberal use of time and space, and throw all those elements onto a single canvas. What do you get? A filmography cultivated by Japanese auteur, Seijun Suzuki, decades before any of these directors approached a camera.

After decades working in such obscurity that the term ‘cult’ wasn’t even applicable, Seijun Suzuki’s name is now forever etched among Japan’s greatest directors. His absurd and stylish take on the yakuza and exploitation genres has continued to delight and mesmerise, while never finding a worthy contemporary. But Suzuki’s rise to pre-eminence was no fairy tale.

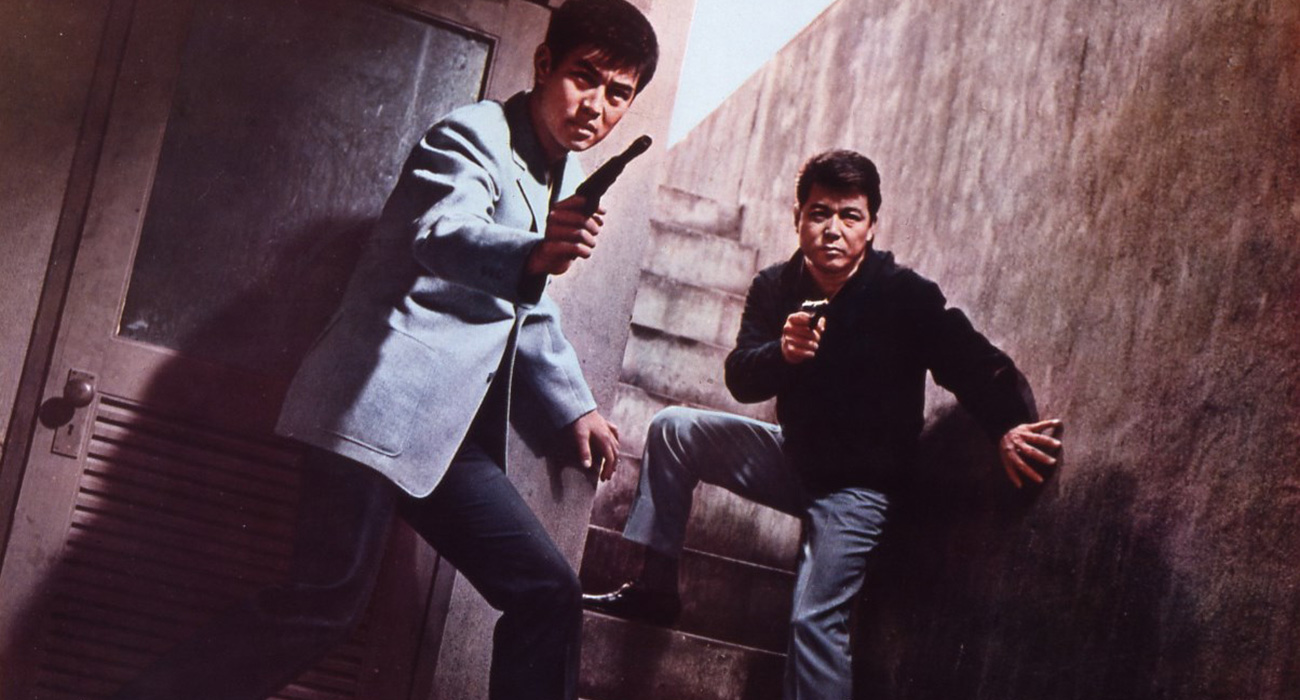

He’s a Tokyo Drifter…

Tokyo Drifter ©1966 Nikkatsu

In Suzuki’s films, his wandering gangsters are shipwrecked in a noir-drenched no man’s land, always anticipating death. Suzuki would recognise that feeling. During World War II, as part of the Japanese navy, Suzuki was shipwrecked twice during battle. He had a comical view of war: “War is very funny, you know! When you’re in the middle of it, you can’t help laughing … I was thrown into the sea during a bombing raid. As I was drifting, I got the giggles.” It’s no wonder his films had an off-kilter sense of humour when it came to the morbid, perverse and violent.

After the war, Suzuki returned to his studies. He failed an exam to become an economy major, so he took another exam to study at Kamakura Academy, a feeder institution for major film studios like Shochiku Studio. He passed that exam and kicked off his film career, becoming an assistant director at Shochiku later that year. Not exactly the most romantic sequence of events, but as Suzuki put it in an interview with Chris Desjardins for the book, Masters of Japanese Cinema, “I’d never dreamed of becoming a movie director.”

At Shochiku, Suzuki worried he’d be stuck as an assistant director and never reach the heights of the studio’s biggest player at the time, Yasujirō Ozu. Then, Japan’s oldest major studio, Nikkatsu, came calling with a paycheck three times bigger and promised Suzuki he’d rise through the ranks quickly. He jumped ship without a second thought.

Nikkatsu followed a Hollywood-style studio system; rigid and factory-driven. Suzuki pumped out three to four films a year, rounding up 40 films in 12 years. All of them played the lower half of double bills, as Suzuki remained a B-movie director for his entire Nikkatsu career. His frequent co-star Jo Shishido said, “[Suzuki] made a huge amount of movies at Nikkatsu every year, all entertainment films or program pictures, like he was putting food into cans on a conveyor belt. He was making movies like no one else at that time.”

“No-name directors like me had zero time,” Suzuki said. “So I had no choice but to stay up all night and never go home.” Being a B-director came with limited resources, but also less on-set supervision. Suzuki explained: “The studio came to me with a script and asked me to make it. But whatever I cooked up after that was up to me.” Most of the scripts Nikkatsu handed Suzuki were Jitsuroku eiga, a popular sub-genre of yakuza films at the time. “It’s not really the genre I’m interested in, but the character of the yakuza,” Suzuki said. “They wander between life and death. As a character, they are more interesting than normal people.”

One Perfect Shot

“I have never made movies as an art form,” Suzuki explained. “I am an entertainer. I make things to entertain an audience.” He squeezed as much as he could from each frame, refusing to spend a spare second on character development or panning across a landscape to build a mood. His films fit among the art-house oeuvre, yet defied art-house tropes every step of the way. If he was bored watching a film, which he easily could be, then he expected the audience would be too.

The scripts Nikkatsu gave Suzuki told the same story each time with the same plot structure. Thus, Suzuki rendered the plot so incomprehensible, it became irrelevant. “In my films, time and place are nonsense,” Suzuki explained. He twisted generic scripts into surreal spectacles and took his audiences on a ride without a roadmap.

“I was always thinking about the style and design of the film,” Suzuki said and arguably, his artistic soulmate was his art director, Takeo Kimura. Together, they squeezed every dollar from Nikkatsu’s limited budgets to create chic, modern sets that made the film look like it topped the double bill, rather than padded it.

Another idiosyncratic feature of Suzuki’s films were the costumes. Who can forget Tetsuya Watari’s powder-blue suit in Tokyo Drifter or Jo Shishido’s dark, wooden-framed sunglasses in Branded to Kill? “Costume fitting is the beginning of character development,” Suzuki said, explaining that the right costume made the actors become their characters more so than any direction he could give.

Jazz and pop-rock tunes are sprinkled throughout Suzuki’s films, because as he put it: “I use music in moments where the audience might become bored.” He used colour for the same reason, embellishing scenes with flair to rouse excitement. “Rather than using the same colour, isn’t it more fun if each scene is a different colour?” Suzuki said. “Generally, a movie is composed of many elements that make a strong impression on the viewer. I call them tricks. I think colour is one of those tricks.”

As much as Suzuki didn’t view his films as art, he still understood the power of his images on an audience. “One perfect image at one point in the film can make the whole film meaningful,” he said. “And that’s what gives me pleasure.”

Suzuki used every possible cinematic tool to grab your attention and force your active participation in his frenzied imaginings. He experimented, and Nikkatsu Studio was his laboratory.

Unleashing the beast

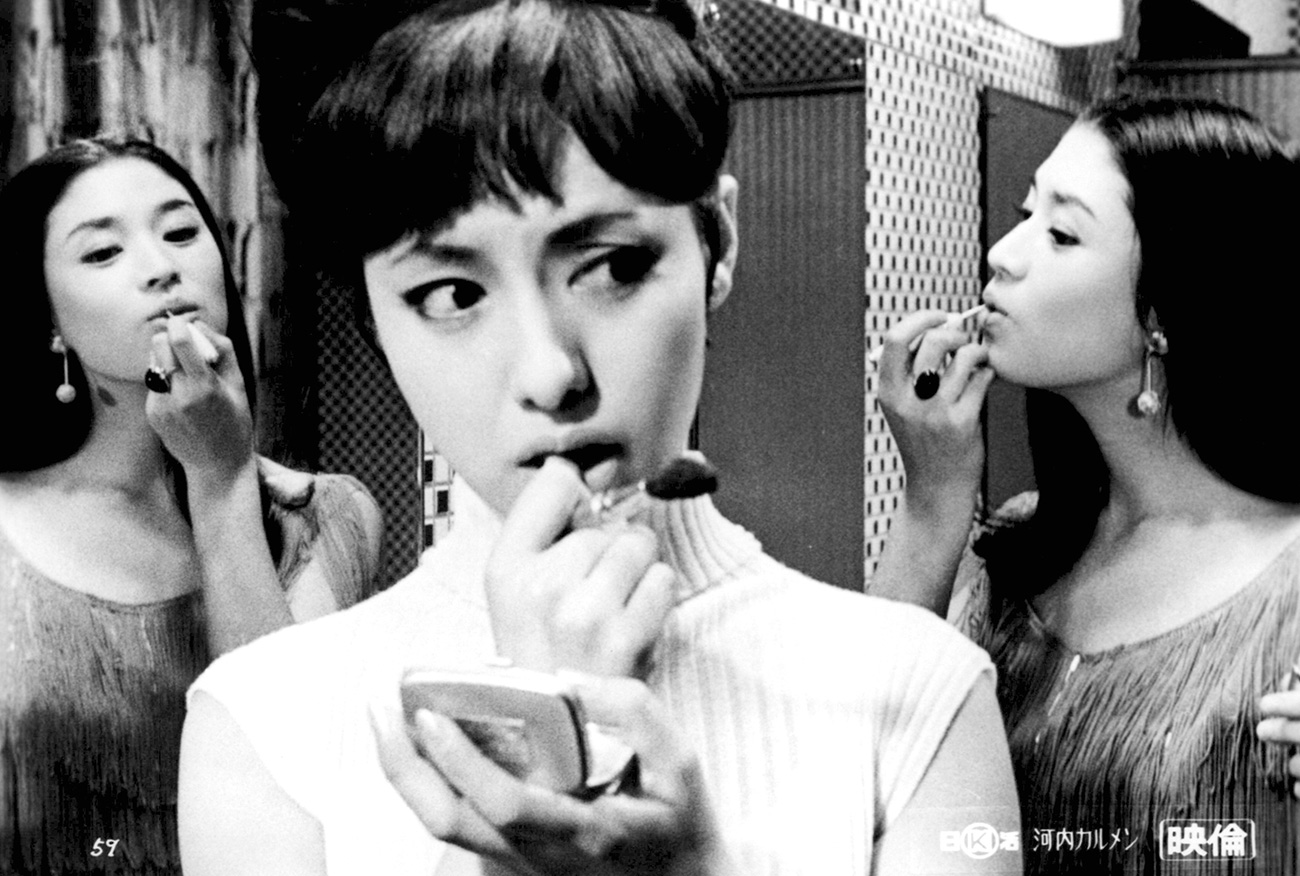

Carmen from Kawachi ©1966 Nikkatsu

For much of his time at Nikkatsu, Suzuki played by the studio’s rules. Then in 1963, he started writing his own rules.

“I feel really the first film that I could call a signature film would be Youth of the Beast,” said Suzuki. Youth of the Beast’s plot doesn’t differ far from Suzuki’s previous efforts but the hallucinatory images, pops of colour, and nonsensical character details, certainly marked a change. No one was making yakuza films quite like this. Youth of the Beast was only a taste to just how absurd Suzuki’s films would become, and spell his demise at Nikkatsu.

At the same time, the French New Wave was thriving by being flippant towards cinematic conventions, Suzuki’s ambitions were taken as insubordination by Nikkatsu bosses. “I was never rebellious,” Suzuki insisted. “I was just mischievous!”

While we’re used to stories of directors defying studio heads, producers and audience expectations to carry out their artistic vision, Suzuki’s defiance was steeped simply in a need to nourish his boredom after having made nearly 30 films with similar actors and plot lines.

“Why make a movie about something one understands completely?” Suzuki said. “I make movies about things I do not understand, but wish to.”

With that idea in mind, Suzuki flipped genres on their head. During his move away from entertainment pictures in the mid-1960s, he created a series of films known as the Flesh Trilogy. Gate of Flesh (1964), Story of a Prostitute (1965) and Carmen from Kawachi (1966) looked at the seedy underworld of nightclubs and prostitution dens from the eyes of the women who populated them. When handed a script for Story of a Prostitute, a romantic melodrama about a “comfort woman” falling in love with an officer, Suzuki took his own war experiences to create a film imbued with stark realism and tragicomic hues. The Flesh Trilogy’s frank depiction of its characters’ harrowing circumstances, further strained Suzuki’s relationship with Nikkatsu.

Suzuki explained in Desjardin’s book: “A director is someone who makes decisions. Say, there’s a particular scene in a film showing a technique of killing someone. It’s the director’s job to decide to make it serious or funny. Those are the kind of decisions that got me into trouble later in Tokyo Drifter and especially Branded to Kill. The decisions I made went against the grain.” When it came time for Suzuki to direct Tokyo Drifter (1966), Nikkatsu slashed the budget in hopes of reigning in the rogue director. This only had the opposite effect on Suzuki and Takeo Kimura. They came up with more imaginative ways of bringing the drifter’s world to life.

Tokyo Drifter reflected a shift in modern yakuza culture, where corporate creed superseded traditional codes and values. The film also parodied the outlandish nature, especially fight scenes, of the yakuza genre. And sometimes, it looked nothing like a yakuza film but more like Singin’ In The Rain, with guns. The theme song is sung a few times throughout the film by lead actor Tetsuya Watari’s sweet voice. The end result was a film that dazzles with its splashes of colour, jazzed up soundtrack and sets that looked like modern art pieces. Naturally, Nikkatsu was furious.

“I was getting warned on every picture I did,” Suzuki said. “There was this one particular producer at Nikkatsu who used to come up to me every time after I’d just finished a film and say, ‘Okay, this it. You can’t do anything more. You’ve gone too far.’”

Suzuki didn’t stop. He only bombastically escalated his style for Branded to Kill. It would be his final film for Nikkatsu.

“In our work, it’s kill or be killed.”

Branded to Kill ©1967 Nikkatsu

“I didn’t intend to make it surreal,” Suzuki said, about Branded to Kill. “But that’s how people see it … I consider that a triumph.”

It’s odd to think a masterpiece like Branded to Kill started off so modestly. Nikkatsu didn’t like the original script and told Suzuki to rewrite it. And Suzuki did, with a team of writers, but often changed plot details and dialogue on set, while requesting ideas from his crew. “In the morning, when he met the cast and crew on the set, he would always ask everyone their ideas on how to shoot the particular scenes,” Jo Shishido recalled. “Everyone would be standing outside the studio scratching their heads to come up with ideas.”

Whoever had the best idea, saw that idea come to life. The film does feel like a slapped together hash of ideas not fully fleshed out, but it’s a thrill to witness for its willingness to be so unabashedly silly (also, Shishido sports what may the first on-screen appearance of a male crop top!).

Branded to Kill didn’t play well with mainstream audiences or critics, and Nikkatsu bosses had enough. Shishido recalls Suzuki’s firing: “After Branded to Kill, president Hori said ‘I don’t understand this movie. You’re fired!’” In Suzuki’s own words, Nikkatsu’s reasoning behind the firing was that his films, “make no money and make no sense”.

Part of Suzuki was relieved to be free of Nikkatsu, but the other part of him was angry. After all, he had lost a job and an income. He sued Nikkatsu for wrongful termination and won, but was blacklisted by all major studios and didn’t make another film for ten years.

Breaking out of cinematic detention

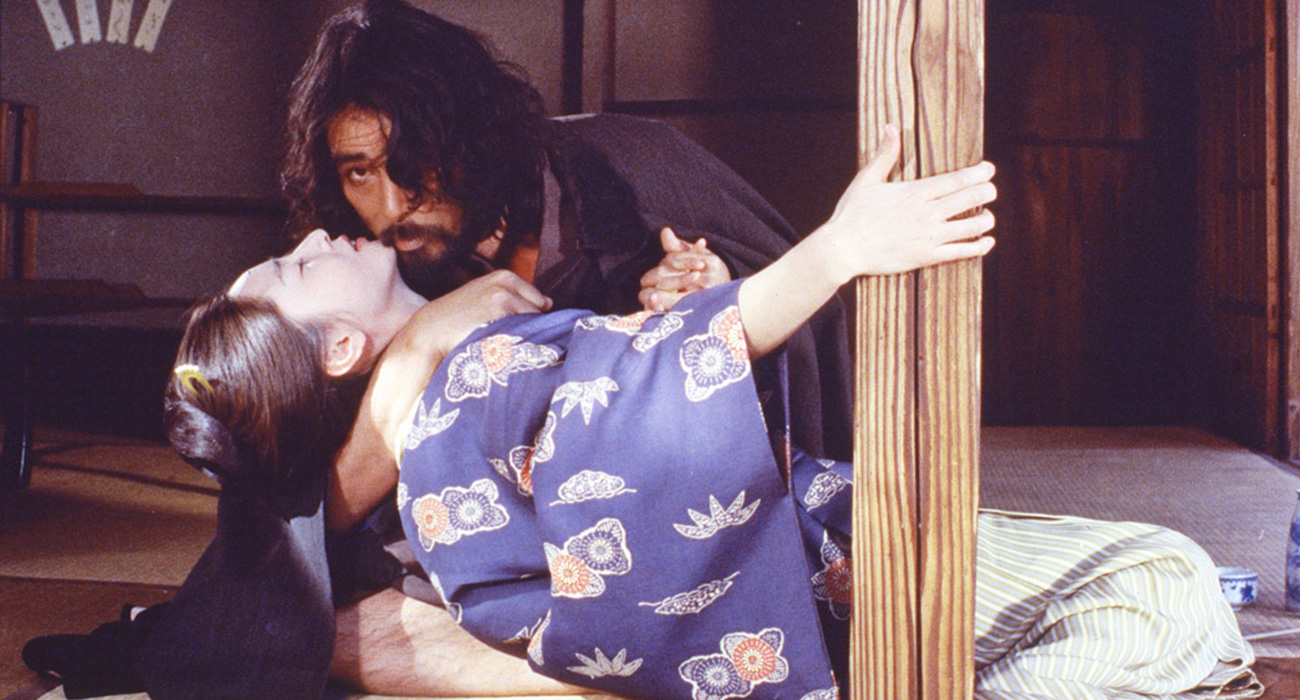

Zeigeunerweisen ©1980 presented by LittleMore Co., Ltd.

Jo Shishido recalls Suzuki’s firing: “Seijun had a lot of friends and supporters in the company. Some of the assistant directors or young art directors, actors too, who worked with him left at the same time in protest.” Film students, critics and intellectuals were also infuriated by Suzuki’s dismissal by Nikkatsu but in 1967, they were a small minority.

In the 1980s, when Branded to Kill made the rounds through film festivals and retrospectives dedicated to the director, the fervor for all things Suzuki grew. “To see that those movies [made for the studio] are received enthusiastically overseas today is something I never dreamed of,” Suzuki said. “I never imagined such a thing happening.”

Interviews Suzuki gave later in life, when people were clamouring to praise him, reflect his genuine bewilderment about the Van Gogh-esque turn of events. “The best thing for a movie is to have a lot of people come to see it when it’s released,” Suzuki lamented. “But back then my films weren’t so successful. Now, thirty years later, a lot of young people come to see my films. So either my films were too early or your generation came too late. Either way, the success is coming too late.”

Suzuki returned as a director in 1977 and worked steadily up until 2005, when he released his last film, Princess Raccoon, at the age of 82. His biggest success during this later period of his life was Zigeunerweisen (1980), which won four Japanese Academy Awards including best director and best film. Suzuki promoted the film by taking an inflatable tent cinema around the country for audiences to see the film. Because, why not?

Health problems kept Suzuki from making more films, right when he could make anything he wanted. He died at the age of 93, on February 13, 2017. His death was announced by Nikkatsu, in a move that finally embraced the legacy left behind by the director they once tried to foil. They certainly didn’t succeed, and we will continue to reap the benefits as modern filmmakers sprint to catch up to Suzuki’s maverick approach and reinvent the best of him while doing so.