Belladonna of Sadness is currently screening on-demand as part of the Perspectives Film Festival in Singapore, held from October 21 – 31, 2021.

For all its reputation as a trippy cult film for cinephiles and anime enthusiasts alike, Belladonna of Sadness is easy to understand. It is straightforward in its usage of the witch as an allegory for a woman’s experience in a patriarchal world. Due to its recent restoration in 4K back in 2016, there has been a resurgence of interest in the film, although I struggle not to raise my eyebrows at the flurry of takes labelling any piece of media that deals with the figure of the witch as ‘feminist’, especially Belladonna.

Produced by Osamu Tezuka and directed by his frequent collaborator Eiichi Yamamoto, Belladonna of Sadness uses Jules Michelet’s La Sorcière, a text on the history of witchcraft as its inspiration. The plot is essentially an occult Tess of the D’Urbervilles: a beautiful peasant woman named Jeanne is brutally raped on her wedding night by the baron of her land enacting droit du seigneur (the lord’s right) and his courtiers. She is then visited by visions of the Devil (who takes a phallic-like form) who promises her power in exchange for her body and soul. As famine, tax and war plague the village under the oppressive rule of the despotic Baron and the nobles, Jeanne eventually cedes more and more to the Devil before finally giving in fully after another traumatic incident and is transformed into a witch. Her powers allow her to both heal and destroy and eventually, her threat to the ruling class has her burned at the stake.

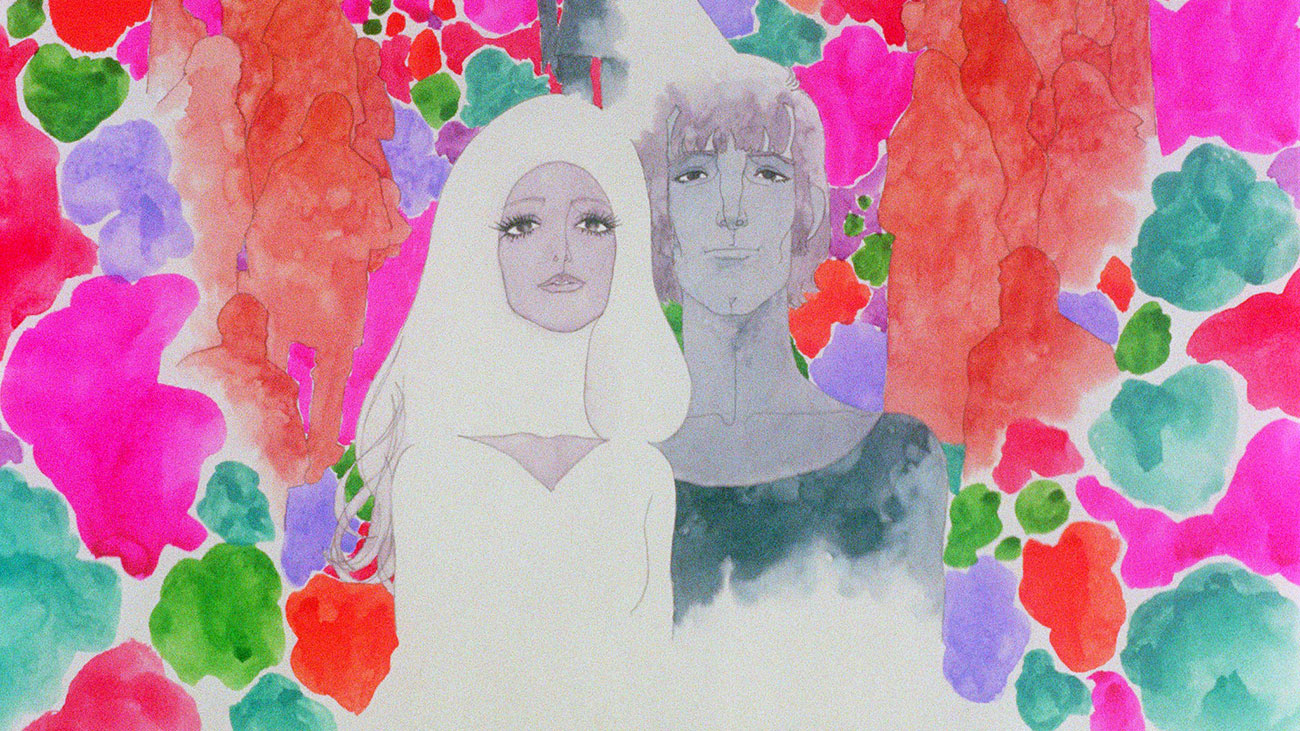

Belladonna challenges stereotypical ideas of Japanese animation and of the medium itself, featuring truly stunning watercolour illustrations that unfold in a static manner. While this may sound jarring for a viewer, the absolute gorgeous nature of the illustrations keeps you captivated with its vivid colours and textural, painterly feel. You can almost feel the brushstrokes and pencil marks in the different illustrations. Art Nouveau was a major influence on the aesthetics of the ’70s and the film is the epitome of Art Nouveau-influenced beauty. The sylph-like character designs of Jeanne and the noble class call to mind the works of fin-de-sciele (turn of the century) artists such as Harry Clarke, Aubrey Beardsley, and Alphonse Mucha. Even the violence is at once evocative and harrowing, such as the expressionistic rendering of Jeanne’s body being ripped in half while she’s being violated and the transformation of the devil from a small, phallic-like creature into a looming, sinister shadow hovering over a wasteland. The pulsating, psychedelic rock score by Masahiko Satoh is also uniquely anachronistic in a film set in medieval France, and a key part of the experience, highlighting the turmoil and insanity in Jeanne’s world.

As stylistically impressive as the film is however, Belladonna also lacks direction. The film’s flimsy left-leaning, post-feminist virtue signaling is especially cringe-worthy: from its weak allusion to Jeanne as Joan of Arc, to its extremely ridiculous coda—suggesting Jeanne’s influence on future generations using the imagery of Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, with the text “… and at the head of the Bastille stood the women”.

At its best, the allegory of the witch’s journey in fiction can be deeply feminist as she represents a transgressive figure in a patriarchal society negotiating and embracing her power and agency. Belladonna attempts to execute such a journey but does so very superficially. The film uses the violent rape of Jeanne, her growing power, her descent into despair and witchcraft to show the audience the evils of the patriarchy and feudalism, yet there is not much depth to this commentary. Yes, the patriarchy is afraid of women with power; yes, a woman’s sexuality is often demonised by society; yes, a class system will always ensure that the working classes are exploited. And what? The film offers no further nuance to these thematic concerns. Indeed, Jeanne is never a fully realised human being, and neither are any of the other characters, who are nothing more than caricatures. It is not to say that sexual violence cannot be depicted in cinema, but most of Jeanne’s actions are reactionary to things done to her. We have no insight as to who this character is. The hypersexual nature of the film is also deeply contradictory as it suggests the embracing of freer sexual mores and female sexuality, yet none of the sex that Jeanne experiences in the entire film is truly consensual or pleasurable. She does not reclaim power or possess any true agency over her body and self at any point. Even her ‘choice’ to fully submit to the Devil and turn into a witch is done out of coercion, with the tiny creature wheedling her at every turn.

It is important to understand that Belladonna was made in the 1970s, where much of the Japanese film industry was in crisis. Many Japanese studios turned to making exploitation films and pinku eiga (pink film) to stay afloat. Tezuka’s studio Mushi Production was already in dire straits and the commercial failure of Belladonna of Sadness led to the bankruptcy of the studio1[1] Restoring a Lost Psychedelic Anime Classic: An interview with the team reintroducing Belladonna of Sadness, Katie Skelly, September 23, 2015: https://www.tcj.com/belladonna-of-sadness-interview/. Meanwhile, the ‘sexual revolution’ was ongoing amidst postwar disillusionment. Context is important in negotiating the conflicting experience in watching this film.

Belladonna of Sadness did push the boundaries of what could be shown on film in both sex and violence, and it showcased a more mature, artistic side of animation as a cinematic medium after mostly being relegated as a genre for children. However, as is the case with cinema occurring during this postwar era around the world, these confrontations with sexuality and extreme cinematic imagery were often done at the expense of women’s bodies, masquerading under the guise of sexual liberty and post-feminism. Sexual violence and battered women’s bodies were often used as a troubling metaphor in cinema for the postwar nation. Still, the beauty of Belladonna of Sadness is undeniable; its visual style and animation remain unique to this day. It very much deserves a watch, especially with the wonderful restoration work done by Cinelicious but this comes with a caveat—this film is most certainly not a feminist depiction of the witch, or womanhood in any measure.