“All of us Japanese are responsible for the war. All of us struggled in the postwar days. Who can throw a stone at whom?”

Love Letter (1953) is Kinuyo Tanaka’s debut feature film, and bears no similarity to a much more famous film with the same name, Shunji Iwai’s perennially popular Love Letter (1995). Nevertheless, with such a title, and what few images you can find on the internet about the film (combined with the brief synopsis of the film: “A sad and troubled man finds a new job five years after the end of WWII, where he writes love letters for other people”) you would be hard-pressed not to think this was a romantic melodrama.

Having achieved success as an actress and well-known for her collaborations with Kenji Mizoguchi, Kinuyo Tanaka directed this screen adaptation of Fumio Niwa’s novel with a script by Keisuke Kinoshita. The film looked at the ‘fallen woman’ genre from a seemingly male perspective, with Reikichi, played by Masayuki Mori as protagonist. Initially, for those familiar with Tanaka’s work as an actress, this might have seemed like an odd choice. Now that Tanaka is in the driver’s seat, shouldn’t she want to tell a story from a female perspective? This is part of Love Letter’s con and the deftness of Tanaka’s direction, starting with the innocuous title. The film deconstructs the romantic melodrama and is a systematic takedown of male hypocrisy, a sympathetic look at the stigma against ‘fallen women’ and what they had to do to survive in postwar Japan, and the hypocrisy of Japanese society towards American influence.

With Reikichi as the story’s protagonist, his hypocrisy and deficit character is more comprehensively laid bare. On the outset, Reikichi is set up as a Brooding Tortured Romantic Hero, while his brother Hiroshi (Juzo Dosan) is portrayed as a Nice Guy. At the start of the film, Reikichi is haunted by the marriage of his childhood sweetheart Michiko (Yoshiko Kuga) to another man and his inability to find her. He is also unable to find work. The subtext is that he has a great deal of ego because of his education, which has partly contributed to his lack of work. When he runs into an old friend Yamaji (Jukichi Uno), he finds work alongside Yamaji writing love letters in English and French for spurned Japanese women to their Western lovers who have abandoned them after the occupation. While Yamaji is sympathetic, friendly and helpful to the women, it is clear that Reikichi looks down on them.

In the context of postwar Japan, women who socialised with American GIs were all conflated with prostitution as Japan’s notorious practice of providing ‘comfort women’ continued after the war to the American GIs. There were the women who were employed ‘officially’ by the brothels set up by the Japanese government and lived near the military base, and then there were also women who socialised with the military men and became their lovers and mistresses to survive; some going on to have babies with them. Tanaka doesn’t mark out the distinctions between the women because in the eyes of the Japanese public, they were all ‘fallen women’.

The Big Reunion: Reikichi (Masayuki Mori, top right) and Michiko’s (Kinuyo Tanaka, top left) reunite at the train station.

It takes the film around 40 minutes—nearly half its runtime—before we finally get to the Big Reunion between Michiko and Reikichi. It feels like a culmination for all of Reikichi’s tortured romantic hero pining. Reikichi searches for an unaware Michiko through a train station, where a crowded train is about to pull away, with her on it. He calls to her, she finally hears, and they lock eyes as she fights her way towards him. The train doors close and pull away, serving as a clever transition to a flashback of their shared history. It is the kind of classic emotional high point you’d expect from a romantic melodrama. For any viewer still expecting a romance though, what unfolds after is decidedly not a romantic reunion. Reikichi proceeds to castigate and pass judgment on Michiko based on what he overheard when she came to request Yamaji’s help to draft a letter for her American lover who abandoned her after she miscarried.

“Why did you let an American soldier have you? Who killed your husband? It could have been the man you slept with.” It is clear his repulsion to her history is twofold, like with all the other women that he writes letters for. He considers these women moral failures, both for betraying Japan by taking up with the enemy, the Americans, and for compromising their virtue. Whether or not Michiko engaged in sex work or was simply a kept woman of an American GI is besides the point — either way, he, like the general public, regarded her as a whore.

Some criticism has been made that Tanaka submits to the Madonna-Whore complex in her portrayal of women with the most discussed scene of the film1Gonzalez-Lopez, Irene and Mayu, Ashida. (2018). Tanaka Kinuyo: Film Director in Tanaka Kinuyo: Nation, Stardom and Female Subjectivity. Edinburgh University Press. Pg. 111, which occurs in the last act of the film. Hiroshi has met with Michiko and tries to persuade her into believing that Reikichi has “forgiven her for her past” and they can start their relationship anew. They run into some streetwalkers who recognise Michiko and call out to her. Hiroshi berates them and tells them Michiko is “not like them”. The portrayal of the prostitutes is what always gets criticism, saying that they are shown to be vulgar and crude and portrayed in a negative light, juxtaposed against the meek and therefore virtuous Michiko. This is a strange interpretation, as the context of the entire scene, from Hiroshi and Michiko’s conversation before they meet the other women to the aftermath, all inform the role of these streetwalkers.

Michiko (Yoshiko Kuga) and Hiroshi (Juzo Dosan) run into old acquaintances from Michiko’s past.

Hiroshi’s comment that Michiko is “not like them” further cements his role as a Nice Guy. It has been written that this line reveals Tanaka’s complicitness with the double standards 2Gonzalez-Lopez, Irene and Mayu, Ashida. (2018). Tanaka Kinuyo: Film Director in Tanaka Kinuyo: Nation, Stardom and Female Subjectivity. Edinburgh University Press. Pg. 111 placed on women when it comes to sex and virtue. This cannot be further from the truth. The camera lingers on Hiroshi’s downcast eyes when he and Michiko converse after and she laments that “whether or not it is one American man or not” she is already seen as beyond redemption, depraved, in their eyes. Whatever explanation she tries to give, she can see the doubt in Hiroshi’s eyes. He is also guilty of being repulsed with her.

Reikichi being the more ‘educated’, moralistic and judgmental of the brothers was immediately disgusted with her, which quickly revealed his hypocrisy to us as an audience. Although Reikichi’s attitude is terrible, it is eclipsed by Hiroshi’s behaviour. When Michiko’s past catches up to her, and Hiroshi witnesses it, his ‘well-meaning’ attitude—which is presented to audiences for a huge length of the film—quickly changes to one of doubt. This scene reveals his misogyny in two ways—first, the internalised misogyny of placing Michiko on a moral pedestal and then second, the outward misogyny of discriminating against women who do not live up to lofty patriarchal ideals of womanly virtue.

In the end, Michiko feels hopeless and commits a desperate act. Some have read this act as the story ‘punishing’ her for her past, which is another bizarre interpretation. It is clear that everyone in the story is a victim to the double standards of Japanese society’s morality that in fact, still persist to this day in most cultures. Michiko cannot forgive herself for what she had to do to survive after the war, placing dual shame on her ‘sexual impurity’ and ‘betrayal of her nation’ by sleeping with an American GI. The men are also victims of the patriarchal values and xenophobia rooted in the society.

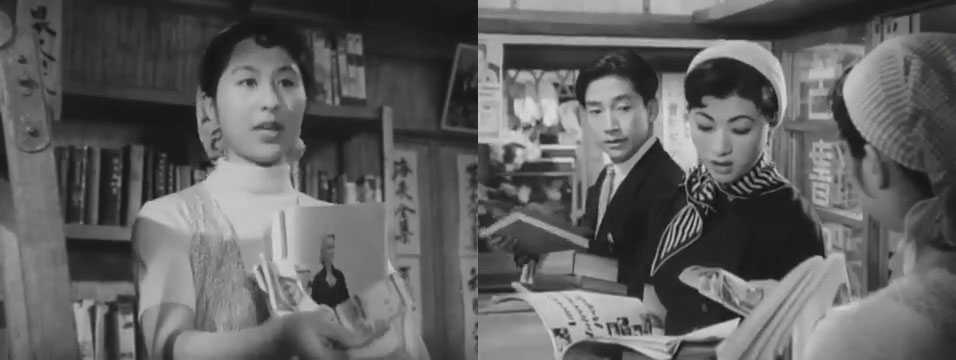

Kyoko Kagawa (left) as a bookstore assistant in Love Letter.

A side plot of the film involves Hiroshi’s flirtations with a girl working at a bookstore specialising in foreign (i.e. Western) publications. As the girl is played by Kyoko Kagawa (Tokyo Story, The Crucified Lovers), she stands out. Hiroshi learns from her about the women trying to sell their American magazines obtained from the GIs to the bookstore. Hiroshi sees an opportunity and sets up a magazine stand taking on the business of reselling their magazines. From afar, Reikichi wears a disdainful expression as he observes his brother. However, Reikichi also understands English and French and was basically living off Hiroshi until he found the job writing English letters to the American GIs who have abandoned their women in Japan. Both brothers depend on these women for their work, yet they pass judgment on them and their association with the American soldiers. The popularity of both the bookstore and magazine stand also highlight American culture’s influence in postwar Japan, despite the public’s regard of them as the enemy. The film reveals yet another layer of hypocrisy of postwar Japanese society through this side plot.

Much of postwar Japanese cinema has explored the effects of war in a more nuanced and complex manner than the West, choosing to focus on the trauma and aftermath left on the civilians, especially women. However this is the first Japanese film I have seen that acknowledges Japan’s culpability with a line as explicit as “All of us in Japan are responsible for the war”. The film stresses on Reikichi’s role as an ‘educated’ military man, meaning his actions in war are far more horrific juxtaposed to whatever he thinks are Michiko’s transgressions.

Kinuyo Tanaka (right) makes a cameo in her directorial debut as a customer of Reikichi’s.

Kinuyo Tanaka was one of the most celebrated actresses of her time, working steadily from the 1920s and enjoyed critical success both in Japan and internationally for her role in The Life of Oharu (1952) before becoming the second ever female director in Japanese film history. However, she had been cruelly derided by the Japanese public back in 1949 after a goodwill trip to America having left Japan in a kimono and arrived back in a Western dress. Her frequent collaborator Kenji Mizoguchi opposed her working as a director, trying to keep her out of the Directors Guild of Japan and she never forgave him for it.3Gonzalez-Lopez, Irene and Smith, Michael. (2018). Introduction: The Golden Era in Tanaka Kinuyo: Nation, Stardom and Female Subjectivity. Edinburgh University Press. Pg. 14 She had played many ‘fallen women’ prior to making Love Letter, and even has a small cameo in the film as another ‘fallen woman’ that Reikichi berates. With her roles in The Life of Oharu and Women of the Night (1948), she explored the absolute bottom of a woman turning to sex work to survive. These basic facts about Tanaka’s career can help inform her work in Love Letter.

It would be interesting to learn more about Fumio Niwa’s novel and how Kinoshita’s script initially read, coming from a male perspective, then translated on screen through Tanaka’s direction. The way Tanaka portrays women and sex workers is never seen through a judgmental black and white lens, and she carefully avoids dwelling on their victimhood. This is in comparison to many of the other great Japanese directors of her time such as Naruse and Mizoguchi, who are no doubt masters of their craft, but whose writing of female characters as constant victims require much needed re-evaluation. Instead, the hypocrisies of patriarchal, postwar Japan are revealed through Reikichi as a source of true psychological violence towards women. In Kinuyo Tanaka’s first directorial work, we see a much-needed female voice that offers a much more nuanced reading of women’s lives in postwar Japan, and especially regarding sex work.