“We’ll live through the long, long days, and through the long nights (And when our last hour comes we’ll go quietly)” is the title for the final track from Eiko Ishibashi’s gentle yet lively score in Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car (2021). The track’s title is adapted from the lines of Sonya’s famous monologue in Uncle Vanya, the play by Anton Chekov that features in Hamaguchi’s film as an experimental theatre production the protagonist Yūsuke Kafuku (Hidetoshi Nishijima) is directing. To exist and live as a human being is a long, confusing, tiring and painful journey. Even more so, to coexist with others is to open ourselves to the possibility that others can inflict those same painful emotions on us, and yet we still persist in seeking those connections. Why? Just like how the title of the track gives no answers, these explorations of living and connecting with others lie at the heart of Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s cinema.

Drive My Car (2021)

“Hamaguchi’s cinema is characterised by a rare attentiveness to the nuances of character and the moment. Particularly moments of rupture where the messiness of human emotion collides via chance, coincidence and radical honesty, causing friction between the characters and society’s expectations,” describes independent film programmer Kate Taylor in the introduction of her interview with the director during this year’s BFI London Film Festival. Hamaguchi subverts expectations of tropes within melodrama to confront relationships, such as in Passion (2008) and Happy Hour (2015). He uses serendipity and surrealist elements to tease out vulnerability from his characters due to the unexpected nature of their situations, such as in Wheel of Fortune & Fantasy (2021), Asako I & II (2018) and Heaven is Still Far Away (2016). And in a nod to his own way of working with actors, Hamaguchi often explores the performative nature of identity and the ability of storytelling and performance to excavate hidden truths—the essence of Drive My Car (2021). When examining Hamaguchi’s recent work and comparing it with his earlier output, there is a clear thread of fascination with communication and connection which the director examines with precision, humour, sensitivity and warmth.

Jun (Rira Kawamura) at her divorce trial in Happy Hour (2015).

Melodrama (Happy Hour, Passion)

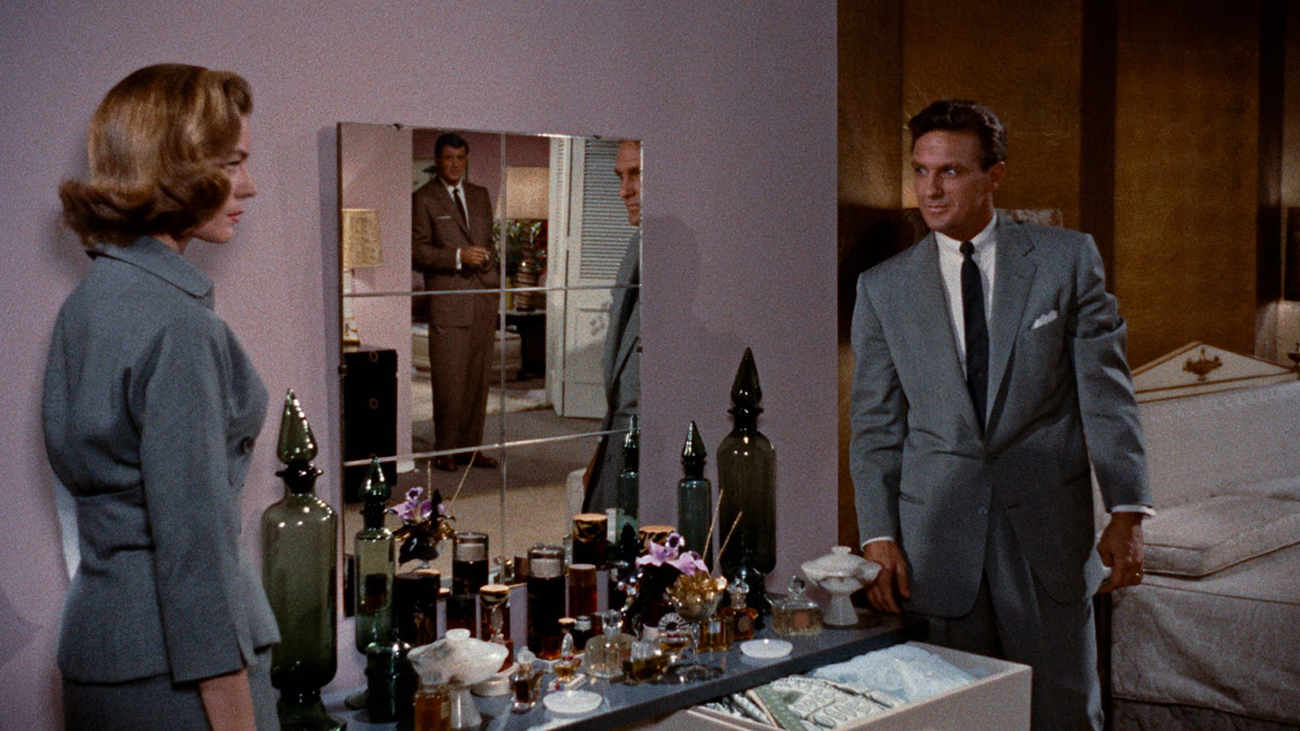

In an interview with Mubi Notebook for Wheel of Fortune & Fantasy, Hamaguchi was asked about his affinity for melodrama in his films and expressed admiration for the works of Douglas Sirk, often regarded as the master of the genre. Stylistically, Sirk and Hamaguchi’s films could not be more different, but a closer examination beneath their surfaces will allow one to see the resonance between both filmmakers’ works—how both are reverent about the delicate nature of human emotions and relationships. Said Hamaguchi on the way melodrama both captures the absurdity, dramatic irony, humour and tragedy of the human condition—“We live seriously, but then again, we do foolish things. This is how we live our lives. That’s the reason why I link my films with the notion of melodrama—because, as simple as it is, I consider life as melodramatic.”

Written on the Wind (1956, Douglas Sirk)

Hamaguchi was seven years into his filmmaking career and on his eighth film (and fifth narrative film) when he broke through on the international circuit with the sprawling, five-hour long Happy Hour (2015) at the Locarno Film Festival. Like many outside of Japan, this was my first encounter with his work, and I am grateful to have experienced the film in a cinema with no intermissions. The film follows a group of four women in their late 30s, whose friendship and own personal relationships are tested when one of the group, Jun (Rira Kawamura), abruptly demands for a divorce from her husband. She states during the divorce trial, “I was killed by my husband.” Hamaguchi’s films often use an incident that is unexpected in the lives of his characters to disrupt the flow of their usual routine and force them to confront things left unsaid and once swept under the rug. In Happy Hour’s case, the ripple effect through the group and their respective families and relationships in the wake of Jun’s divorce is quietly violent in its impact.

When you lay out the incidents that unfold throughout the story—Jun’s seemingly impulsive divorce and decision to skip town, Sakurako’s (Hazuki Kikuchi) contemplation behind her colourless marriage and her teenage son knocking up his girlfriend, Fumi’s (Maiko Mihara) husband working with a young female novelist who is attracted him, Akari’s (Sachie Tanaka) awkward romance that also involves the man’s sister possibly being attracted to her as well—it could all unfold into a very garish soap opera in the wrong hands. But Hamaguchi allows these classic tropes from melodrama to play out in an observational, almost documentary-like manner. Happy Hour was also distinct in its use of non-professional actors, allowing audiences to fully immerse themselves into the stories and actors without any preconceived notions of the actors behind it. For international audiences, this may not seem like a big deal since many would think they’re generally unfamiliar with Japanese actors, but Hamaguchi has previously worked with recognisable Japanese actors whose personal lives unfortunately are the subject of scrutiny. By using non-professional actors for this particular film, Hamaguchi allows for a greater level of objectivity and instinct to take over both his actors and audiences as these dramatic situations unfold.

Nao Okabe and Aoba Kawai in Passion (2008)

This observational direction is most apparent in Happy Hour, but also in his first film Passion (2008), which similarly has many common tropes of melodrama such as infidelity and unrequited romantic feelings. Hamaguchi’s fascination and respect for the little fires in the everyday lives of ordinary people resonates in this graduation project from film school.

We follow a group of friends who meet for a get-together when Kaho (Aoba Kawai) and Tomoya (Ryuta Okamoto), the couple in the group, announce their impending marriage. Over the course of the night and following day, the friendships within the group are tested as it is revealed that Tomoya has had an affair with another member within the friendship group (Fusako Urabe) and long pent-up emotions between all the friends are exposed. Although its presentation is akin to the flat, unsophisticated look of mid-00s J-Dramas, the film is ripe with all the seeds of what Hamaguchi would perfect over the course of his career: the understanding that our hidden desires, secrets and things left unsaid, and miscommunication is the melodrama of everyday life. And just like every film of his, there are no easy reasons for people’s motivations, or even answers at all to the confusion that plague our own personal growth and our relationships with others. All we can do is to try and live.

It’s fascinating to go back and examine Hamaguchi’s work pre-Happy Hour. For all its rough edges, Passion was the one that sunk its roots in me the most because it had all the themes that would recur consistently throughout his films. Moreover, his graduate film also marked the start of his collaborations with actors Aoba Kawai, Fusako Urabe, Nao Okabe and Kiyohiko Shibukawa, who would become key collaborators of his.

Erika Karata in Asako I & II (2018)

Surrealism (Asako I & II, Heaven is Still Far Away)

Happy Hour was such a powerful statement that everyone was waiting eagerly for Hamaguchi’s follow-up. Asako I & II (2018) was lighter both literally and metaphorically—clocking in at exactly 2 hours, and is both an enigmatic yet detailed study of identity and relationships. After the psychological realism of Happy Hour, the premise of Asako appeared precious at best and far-fetched at worst: a young woman falls love at first sight with an impulsive, charismatic man who sweeps her off her feet. He disappears suddenly one day and then she meets another man who looks identical to him, but with a completely different personality.

Based on a novel by Tomoka Shibasaki, Hamaguchi stated in an interview with Film Comment that he was drawn to the story because the situations could seem “out there” but were “written in such detail that you go along with it”. In the telling of the film, he used genre conventions in romantic dramas, comedies and psychological thrillers to cue the audiences. “One of the things I wanted to do was to have realism and surrealism coexisting: allowing something real to come out of this absurd situation, or to have some absurd quality rooted in the reality that we crafted.” In Asako, his camera language is far more experimental and stylish, with doubling and doubles recurring in both imagery and narrative structure, but he balances it out with a visual palette that remains sparse and grounded in realism.

Although the story appears to be a depiction of romantic delusion, Asako is more of a coming-of-age tale and ghost story. The film is less about Asako (Erika Karata) and her relationships with Baku and Ryohei (both played by Masahiro Higashide) but rather, a detailed psychological exploration of a young woman. This is apparent from both the English title, and the original Japanese title “Netemo sametemo” from the novel which translates to “Whether asleep or awake”. Both are spot-on titles that reveal the dreamy, surreal elements of the film while acknowledging the multitudes to Asako’s personhood. Is it simply about Asako maturing into an adult and the two men representing two different stages of her life? Is it about the type of life she chooses? Is it about discovering who she is and who she chooses to be? The open ending leaves room for more interpretation: whether or not you see it as bittersweet or tragic or hopeful or a realistic compromise says something about who you are. By contrasting genre conventions and showing restraint through leaving the absurdities in the plot unexplained, Hamaguchi allows realism and surrealism to coexist in Asako, opening the story up to a myriad of interpretations.

Asako is a polarising work in Hamaguchi’s canon following Happy Hour, but the film remains highly personal and deeply impactful to me. I say this about many of Hamaguchi’s films, but perhaps Asako will always have a special place in my heart. The character of Asako represents the detailed, unrealised anxieties of myself as a woman struggling to find her place between dreams, disillusionment, reality and the ghost of one’s past, present and future.

Hyunri, An Ogawa and Nao Okabe in Heaven is Still Far Away (2016).

Hamaguchi created yet another ghost story prior to Asako, in the short feature Heaven is Still Far Away (2016). It was originally conceived as a gift for those who helped crowdfund Happy Hour. Clocking in at 38 minutes, it shows how crucial short films are for auteurs to experiment with ideas.

We follow the mundane life of Yuzo (Nao Okabe), a mosaic engineer for porn videos, whose flatmate is Mitsuki (An Ogawa), a high school student. When a film student Satsuki (Hyunri) approaches Yuzo for an interview about the death of her older sister Mitsuki, this curious little ghost story unfolds into a story that somehow manages to feature many key Hamaguchi elements. Satsuki and Yuzo’s lives have both been irrevocably affected by the death of Mitsuki. Yuzo is literally living with her ghost as the only person who can see and hear her, while Satsuki is trying to gain clarity on her sister’s death through the making of a documentary about the impact Mitsuki’s death had on the lives of the people who knew her.

Thematically, the film is simple as it examines grief, trauma, catharsis and closure. Conversations are straightforward and to the point: Satsuki says as much that it would be untruthful to say the film was for Mitsuki. It’s a form of catharsis for herself—“I do know one thing. It’s that I can’t move on without doing it.” It’s an important choice that Hamaguchi makes not to focus on how and why Mitsuki died, but rather how Satsuki and Yuzo live on, playing the fantastical element of the story straight.

The film’s most beguiling element however, lies in Hamaguchi’s persistent fascination with performance and who we become through it. Much of the film takes place with Satsuki interviewing Yuzo on-camera for her documentary, and the conversations and events that unfold, including instances where Mitsuki appears to take over Yuzo’s body and communicate with Satsuki. Satsuki, a sceptic, hovers between cynicism (that Yuzo is taking advantage of her grief) and hope (wanting to communicate one last time with her dead sister) as she breaks down, ironically, behind the camera as the director while Yuzo appears calm on camera in a seeming performance of Mitsuki’s mannerisms.

Fusako Urabe in Passion (2008).

Coincidence and Communication (Passion, Wheel of Fortune & Fantasy)

One of the most rewarding aspects of a Hamaguchi film are the performances. Hamaguchi is an actor’s director—able to see the potential in his actors by instinct, and also use them to ground his stories. He teases out fantastic, nuanced performances from his recurring cast: Aoba Kawai, Fusako Urabe, Kiyohiko Shibukawa and Nao Okabe, who were all in his first film Passion. Kawai, Urabe and Shibukawa would all appear once again in Wheel of Fortune & Fantasy, delivering exceptional, surprising performances.

For all three actors, the characters they play in Wheel of Fortune & Fantasy subvert their original characters in Passion. Shibukawa, who is most well-known for playing villains or yakuza characters throughout his filmography, plays the ascetic, strait-laced professor Segawa with great tenderness and depth for what could be a stereotypical performance in the second short, “Door Wide Open”. Given only sparse dialogue, Shibukawa finds a way to intrigue audiences and create a fully fleshed-out character in the segment, through simple, short gestures as he attempts to resist being honey trapped. This is in sharp contrast to his character in Passion, who is the boorish, if well-meaning member of the friend group who says what he thinks and has no airs about him. His brutal honesty provides a perfect foil to the charming and handsome Tomoya (Ryuta Okamoto), who has been told by multiple people, including his potential mother-in-law that he evokes a complete lack of sincerity.

Top: Fusako Urabe and Aoba Kawai reunited in Wheel of Fortune & Fantasy (2021) | Bottom: Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung in In the Mood for Love (2000).

In Passion, Kawai and Urabe play sort-of love rivals: Urabe is the third-party in Kawai’s character Kaho’s relationship. In “Once, Again”, the third short from Wheel of Fortune & Fantasy, the pair instead depict an extraordinary and magical connection borne by coincidence.

Set in the near future where a computer virus has crippled the internet, we return once again to traditional forms of communication such as letter-writing. This “futuristic” set-up is simply a way for Hamaguchi to explain away issues the characters face that could have been solved through social media and the internet. Instead, like his use of melodrama, he forces the paths between unsuspecting parties to cross, somehow creating a more authentic and honest bond. Natsuko (Urabe) returns to Sendai to attend her high school reunion, only to run into Aya (Kawai), who she mistakes as her first love. Aya meanwhile, thinks Natsuko may be a former classmate whose name she has forgotten. Aya offers a startling gesture of kindness in the awkward and possibly humiliating situation Natsuko finds herself in. She offers to role-play the ex-girlfriend so that Natsuko can release the feelings she had repressed and kept in all these years. It’s a scene not unlike the heart-breaking role-playing scenes in Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love, and equally hypnotic. Through the role-play, Aya’s repressed memories and feelings from her past are reawakened.

The ending of “Once, Again”, as with all three short stories is highly satisfying, and to spoil it would be to ruin the unadulterated, serendipitous beauty of that moment. The final line takes on a special extra meaning as well, when you learn that this segment was filmed during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, more than a year after Hamaguchi had completed the first two shorts. The tonal shift between the first two shorts compared to “Once, Again” is obvious. It’s lighter, freer, and less tense, ironic considering the circumstances in which it was made.

A table read scene in Drive My Car (2021).

Performance as Truth, Performance as Identity (Drive My Car & Others)

“Chekhov is terrifying. When you say his lines, it drags out the real you. Don’t you feel it? I can’t bear that anymore,” says Drive My Car protagonist Yūsuke, when questioned as to why he will not be playing the lead role of Uncle Vanya in the production he is directing.

Hamaguchi often uses performance—an act rooted in fiction and artifice—as a way for his characters to release repressed feelings and communicate with each other when words fail. “Once, Again”, as the final story in Wheel of Fortune & Fantasy therefore acts as a perfect segway into Drive My Car. The film is his most technically accomplished work to date, the writing at its most dense and complex, and in it, he also reaches the peak of his endless fascination with performance and identity.

“My workshops are basically having the actors not perform but read the text over and over, and for these readings I ask my actors not to add any nuances or inflections. It’s more about reading the text aloud, over and over, until they can almost say it automatically, and there comes a moment when I can hear it in their voice—a certain weight or thickness—and the words that are written are completely absorbed into the actors,” said Ryusuke Hamaguchi in an interview with Film Comment for Asako I & II.

Touching the Skin of Eeriness (2013).

Hamaguchi had mentioned briefly about this process in previous interviews about how he worked with the non-professional cast of Happy Hour, but we finally get to witness it play out through the numerous table reads in Drive My Car. Yusuke’s methods bewilder his actors initially. His production of Uncle Vanya is an experimental one, using a cast of international actors who deliver their lines in several different languages including Japanese, Korean, Tagalog, Mandarin Chinese and Korean Sign Language. They don’t understand each other in terms of language, but their body and instincts do.

When you go back and visit Hamaguchi’s earlier work, you’ll find this idea littered through his filmography. There are the long stretches of theatre workshops in Happy Hour and the entire plot of Intimacies (2012). There is the homoeroticism in Touching the Skin of Eeriness (2013) and The Depths (2010), brought to the forefront through performative physical intimacy. The experimental dance classes in Touching the Skin of Eeriness where friends Naoya (Hoshi Ishida) and Chihiro (Shota Sometani) dance skin-to-skin are where they communicate the best with each other. Meanwhile, the entire plot hinges on their complete inability to communicate with each other in a healthy manner. In The Depths, photographer Bae-Hwan (Kim Min-Jun) attempts to capture something raw and authentic in his model-muse Ryu (Hoshi Ishida). Although Ryu is the obvious object of desire, he also wrestles back agency as the one who desires as well through his performance on camera.

Kōji and Janice’s audition scene in Drive My Car.

Then there are moments where the lines between performance,instinct and authenticity are blurred, such as during the “on-camera” scenes in Heaven is Still Far Away, in the play-acting scenes in Wheel of Fortune & Fantasy. In Drive My Car, there are the stories told by Oto (Reika Kirishima), Yusuke’s wife, which she spins during sex. We discover that these stories are perhaps not just creative fancies, but a performance of her hidden self. This inexplicable authenticity where performance becomes truth, perhaps, is what Maya, Asako’s theatre actress friend, was criticised for lacking in Asako I & II.

This theme culminates quite spectacularly in Drive My Car, where one of its most electrifying scenes is the audition scene between Kōji Takatsuki (Masaki Okada) and Janice Chang (Sonia Yuan). Both characters are strangers auditioning for Uncle Vanya in a very emotionally uncomfortable scene. Kōji delivers his lines in Japanese, Janice in Mandarin. It is initially jarring and requires the audience to get used to it. It is so for Kōji and Janice as well, who have to rely on what they know of the script and their scene partner’s body language to know when and how to deliver their own lines. It starts off awkward, but eventually builds to something quite startling, akin to the Betty Elms (Naomi Watts) audition scene in Mulholland Drive.

The Renaissance of Ryusuke Hamaguchi

2021 was a major year for Hamaguchi, with his anthology film Wheel of Fortune & Fantasy (2021) winning the Silver Bear at the Berlinale early in the year, and Drive My Car winning both the Jury Prize and Best Screenplay awards at the Cannes Film Festival. Drive My Car has also received four nominations for the upcoming Oscars, including Best Picture. He has been compared to many filmmakers, from Abbas Kiarostami, Hirokazu Koreeda to Hong Sang-Soo, but truthfully, it’s hard to see why these comparisons are made since his fixations, style and writing are extremely distinct and unique, even when it was at its roughest and most unpolished in his early films. It’s easy to overlook his leaner works like Heaven is still Far Away and Wheel of Fortune & Fantasy for meatier cuts like Happy Hour and Drive My Car, but without the former, the latter would not exist, serving an important purpose for Hamaguchi to experiment creatively in both his writing, and technically.

Fumi (Maiko Mihara) in Happy Hour (2015).

On a personal note, 2021 was the most traumatic and painful year of my life. Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s films were a significant source of hope and comfort. Experiencing his early work including his debut film Passion (2008) and his latest two all in the span of a few months has been a rewarding experience. It has made me reflect on what I love about storytelling, and why I am so drawn to his stories. He explores the infinite possibilities of human relationships and connections in all their beauty and awkwardness and messiness. We will always long for intimacy and yet be hopelessly clueless in knowing ourselves and communicating with each other, resulting in repressed emotions, hurt and deep psychological trauma. However, we continue to persist despite it all, and continue to live, and continue to try to reach out to another human being. Our own self-preservation and defence mechanisms will always work their way to protect ourselves from honesty and vulnerability, but if we can break past these subterranean fears, we can perhaps find connection with another human being. And then perhaps, living through the long days and long nights won’t be so bad.