Editor’s Note (February 21, 2017): This piece has been altered to more accurately cite and reflect the history of violent protests in South Korea.

———

Ten years ago, Bong Joon-ho’s genre-defying monster movie The Host was released in its native South Korea. Effortlessly switching between horror, family drama, and black comedy, The Host’s critical and box-office success was as large as its ambitions and scope. With an estimated budget of $10 million USD, considered relatively large by Korean blockbuster standards at the time, the kaiju film quickly recouped its costs, earning $17.2 million domestically within the first four days of release. This success was not contained to national borders, however, earning more than $2 million at the United States box office and nearly $90 million worldwide. International critics were similarly enthralled by the creature feature, ranking 16 in the best reviewed films of 2007 on Metacritic.

While the slimy fish monster that terrorises Gang-du (Song Kang-ho) and his family is often the focus of many international reviews, much like its antagonist, there is much more hiding beneath the surface of The Host. The film’s biting social commentary and historical references, many of which are concerned with American-Korean relations, has also drawn the attention of international critics and moviegoers.

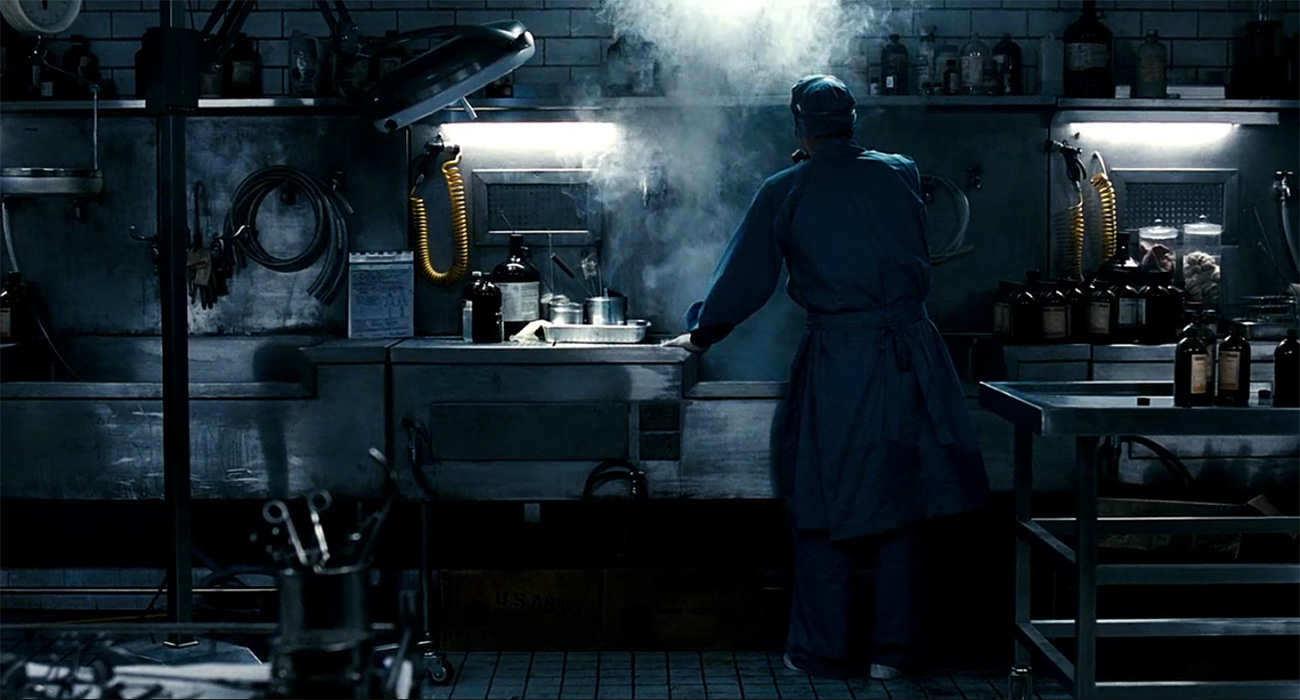

From the subdued opening scene, Bong’s commentary on America’s continued presence in South Korea is overt. The scene is a recreation of the 2000 McFarland case, in which an American military employee ordered staff to pour 90 litres of the carcinogen formaldehyde into a drain which connects to the Han River. The Host’s fictionalised version serves not only as a direct reference to the event, but the American mortician’s (Scott Wilson) constant interruption and condescending attitude towards the younger Korean doctor (Brian Lee) implies an unequal power dynamic between the two nations and disinterest by the U.S. towards the consequences of their actions. This sense of carelessness towards the local population re-emerges by the end of the film in a scene between protagonist Gang-du and an American doctor (Paul Lazar), implying the United States’ efforts are as perhaps as superficial as the military’s operating room. As Gang-du tearfully claims no-one would listen to him, the scientist ironically ignores his pleas before revealing in English that there is no virus, assuming that Gang-du would not be able to understand, again suggesting an attitude of superiority over Koreans.

This critical view of American interference runs throughout the entire film, perhaps most obviously through the use of ‘Agent Yellow’ to destroy the creature. The weapon is a very thinly-veiled stand-in for Agent Orange, a herbicide used by the United States during the Vietnam War which caused widespread health issues and environmental damage. While the devastating effects of weaponised herbicides are only briefly touched upon by Bong, with protesters shown with bleeding ears and breathing difficulties, historical opposition to their use is well-represented by protest signs demanding a stop to spraying.

However, America is just one target of The Host’s socio-political satire, with Bong also taking aim at a range of major domestic issues. Bribery and corruption in the country is exhibited through the actions of Nam-il’s (Park Hae-il) former friend turned snitch, while inefficient support for the lower class is suggested by the homelessness of Se-joo (Lee Dong-ho) and Se-jin (Lee Jae-eung). But perhaps the most prominent national issue to emerge from The Host comes through its third act where youth unrest and displeasure towards government policy becomes prominent. Older brother Nam-il encapsulates the political protests for democracy in the 1980s and early 1990s, employing violent methods which another character comments as being out-dated. Meanwhile, the peaceful tactics of the younger protesters and mass presence of a police force reflects modern Korea, where flag waving, sit-ins, and chanting surrounded by hordes of police take precedence over cocktail throwing.

Therefore, the film’s original title of “Monster” is more than fitting as Bong’s satirical take on the public’s discontent with the Korean government and stationed American military personnel forces the audience to consider what, or who, the actual monster is.

Creating a monster: Gojira and the origins of kaiju cinema

The Host is far from the first kaiju film to criticise the actions of America in a foreign nation. In fact, arguably the most iconic monster series of all-time began as a statement on the United States’ air attacks of Japan. Gojira (1954, dir. Honda Ishirō) is hardly subtle in its allusions to the 1945 nuclear bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Multiple times it is stated that the titular monster is a direct result of radiation from the nuclear bombs, and in itself could be considered a metaphor for the bombs themselves. Godzilla is shown to leave a trail of radiation after attacks, a direct reference to the ongoing environmental and health effects after the event.

Despite Godzilla’s origins and radiation breath, the possible related metaphors extend further than the blasts that ended the Second World War. Long shots of Godzilla’s ominous shadow amongst the flames engulfing Tokyo draws parallels to the devastating firebombing raids of Tokyo, which director Honda witnessed first-hand. Also evident during the aftermath of Godzilla’s attack is a clash of ideologies and moral predicaments, most notably the dilemma of whether to use the “Oxygen Destroyer” weapon. Fearful that the use of his invention could facilitate a global trend of revenge warfare, Dr. Serizawa (Hirata Akihiko) poignantly remarks, “If used once, politicians all over the world will want to use it. Bomb versus bomb, weapon versus weapon.” Although the extensive Cold War was only in its beginning years when Gojira was released, Serizawa’s statements encapsulate the unease and fear that permeated the decades-long period as the United States and Soviet Russia engaged in a nuclear arms race.

Honouring tradition: Big Man Japan and its parallels to The Host

While successive entries in the Gojira series seem to concentrate more on epic battles between giants than social messages, Big Man Japan (2007, dir. Matsumoto Hitoshi) proves that modern Japanese kaiju cinema can still deliver satire alongside spectacle. Big Man Japan is a curious mix of slice-of-life mockumentary and bizarre CG kaiju fights. Following middle-aged divorcee Daisato (Matsumoto Hitoshi), who grows 30 metres tall when electrocuted to fight kaiju on television, the film’s surprisingly grounded social commentary comments on everything from loss of meaningful tradition and the overwhelming prevalence of advertising in modern Japan.

However, it is the film’s final ten minutes which have attracted the most attention for both its absurdity and unapologetic statements on the United States and Japanese respective military power. Following Daisato’s failed second encounter with a demon kaiju sent from North Korea, the film abruptly switches to live-action and a family of red, white, and blue-clad Ultraman-esque heroes appear. Although there are early mentions at commentary on the Japanese public’s changing perception of the United States, the undressing and humiliation of the North Korean demon by human heroes, led by “American Hero Super Justice”, strips away any remaining doubts that Big Man Japan is just another surface-level kaiju brawler. Like The Host, the final scenes could be interpreted as a comment on the United States’ proud military involvement in foreign nations. However, Daisato’s cowardliness and lack of impact during the final scene suggests that Big Man Japan also wonders whether Japan is overly dependent on the United States due to an arguably then-limited capability of the Japanese military, following peace clauses in their post-Second World War constitution.

———

Since its release, The Host not only continued the tradition of kaiju films, mixing the metaphorical and meaningful with fantasy, but also launched the international careers of stars Go A-sung, Bae Doo-na, and Song Kang-ho. It also proved that Korean audiences were, and still are, interested in more than the thrillers and historical dramas that dominated the top-grossing Korean charts prior to 2006.

With Bong’s return to the genre, Okja, slated for a 2017 release which promises an international cast and the story of a multi-national conglomerate poised at stealing the monster best friend of a young Korean girl, expect further commentary on modern society and US-South Korean relations with the emotional, relationship-centred stories that director Bong has become known for.