It’s no secret that there has long been a need for more female stories to be told in cinema. While every part of the world is responsible in righting this imbalance in media representation, East Asian cinema has historically had a fairly decent track record in telling a range of female driven stories, both in the commercial and arthouse realms.

Great Japanese directors such as Yasujiro Ozu, Kenji Mizoguchi and Mikio Naruse were known not just for their deeply humanist stories but also for their unflinching look at the oppression of women in society through their films. Over in Hong Kong and China, directors like Zhang Yimou and Stanley Kwan made conscientious efforts to make films that often dealt with complex but ultimately tragic portraits of women.

The contribution in telling female stories in cinema by all these directors is immense, but often we fail to discuss or give enough attention to the more commercially marketed female driven films. This seems silly when you think about how not everyone’s tastes are geared towards arthouse films, even if that is where the more complex and diverse stories are found. While arthouse film directors have helped to pave the way for complex writing in female stories, they often share a common theme of tragedy, which is why lighthearted films are needed all the more; if only to even things out.

The strive for female representation in films should therefore involve further production and discussion of female-oriented commercial fare like romantic comedies or high school romances, genres that are traditionally looked down upon.

This brings us to Our Times, the coming-of-age smash hit from Taiwan which has broken box office records and won the hearts of fans all over Asia in 2015. Its financial success not only signifies the film’s accessible and wide appeal to the masses but also symbolises a triumph for its female director and writer Frankie Chen, who sought to make a commercially successful, lighthearted and well loved movie with a relatable female protagonist.

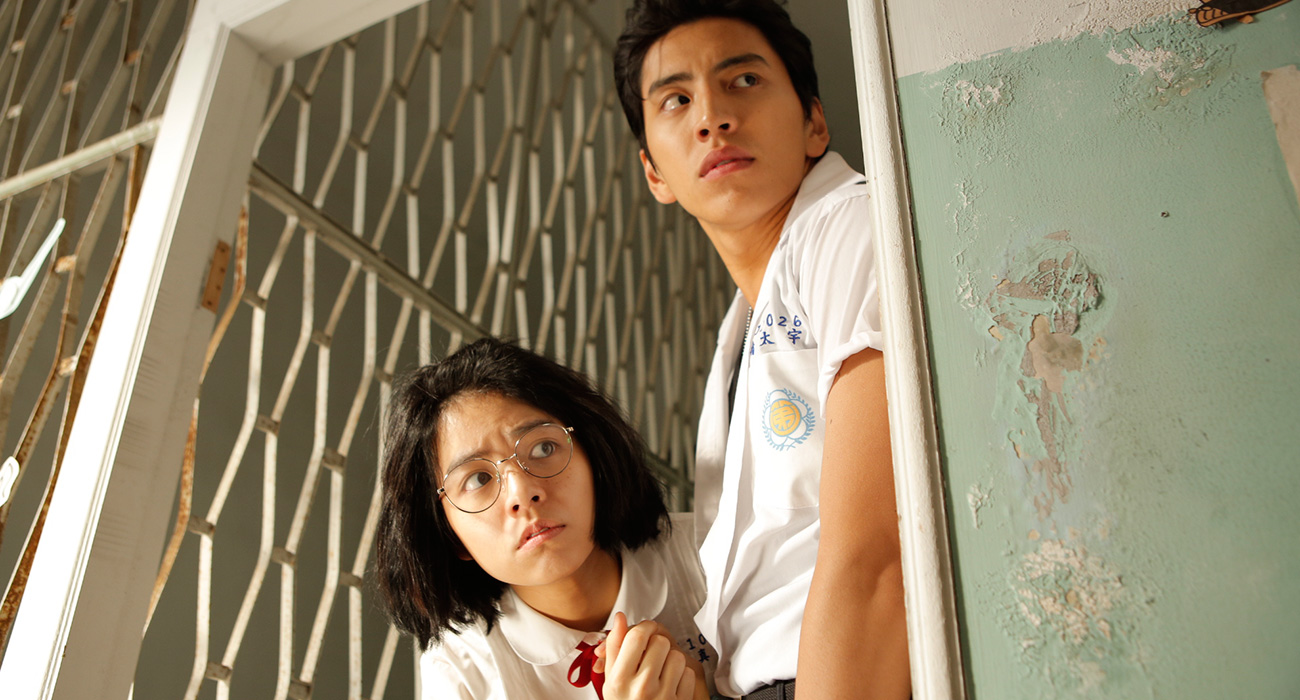

Our Times takes inspiration from director Frankie Chen’s own teenage years and tells the story of Truly (Vivian Sung), a perfectly ordinary teenage girl trying to juggle her awkward teenage years, school life, and fangirling over her favorite idol, Andy Lau. She’s an instantly recognisable and relatable character because she is who most teenage girls were and are to this day. She has a crush on the school’s most popular guy, Ouyang Fei Fan (Dino Lee). When she foolishly sends a chain letter to Hsu Tai Yu (Darren Wang), the school’s most feared gangster to protect Ouyang, shenanigans ensue. Along the way, Tai Yu and Truly become determined to break up the budding relationship between Ouyang and the school belle Tao Min Min (Dewi Chen) and instead end up falling for each other.

Sure the story might appear too familiar and a touch simplistic, but so what? Should it matter if Chen doesn’t tread new ground? Lighthearted commercial films provide a form of hope and fantasy for its viewers, and there is nothing wrong with a bit of escapism for audiences. And in telling a familiar story in a fun environment, what Chen does give to her audience is a thoughtful romance where the leading male and female characters learn how to treat each other as equals and respect each other (they start out not at all liking or respecting each other).

The popular trope to pair up characters from different social backgrounds or cliques, as a riff off the idea that “opposites attract”, is one that’s often used in high school films. Our Times uses this trope as well, but what it does differently from its other film counterparts, like Grease or High School Musical, is show the actual progression of how these characters see past their surface differences and befriend each other before developing deeper feelings, which is far more realistic. Instead of solely relying on the presumption that “women love romance”, Chen made the earnest effort to show her target audience characters they could connect with. She does this by giving us that progression in the characters and their relationships first.

Additionally, Chen’s choice to set the film in the ’90s — an era where a majority of her target audience would have grown up in so that they could, like Truly, reflect on who they were as young people — is also smart as the filmmaker takes her audience back into the present day where we move past Truly’s coming-of-age as a teenager and show who she is now as a woman. Truly’s reflection on her carefree teenage self also leads her to make bolder and better decisions about her life now as a woman as she draws strength from who she once was.

By reconfiguring these standard genre tropes in a nostalgic setting, Chen manages to achieve two great things. In the first instance, Chen demonstrates that you can tell a meaningful story about women and their relationships in a commercial space, especially one that’s not afraid to be silly in the way that Asian high school films usually are. Secondly, she has made the film in such a way that its appeal was not lost on a mass audience, thus making Our Times a strong case for other women to be able to tell the kind of light-hearted stories they want to tell; the kind of stories we should be seeing more of in cinemas.

Contrary to what most people in the industry think, the success of commercial films like Our Times indeed reveals that audiences do respond to films directed by women, or films about women, as Frankie Chen has proven. Back in 2013, actress-turned-director Zhao Wei too found a positive commercial response to her debut film, So Young. Female audiences consume just as much media and pop culture as their male counterparts, if not more. There is no reason that the stories they want to see should be considered as frivolous fantasy when the stories most men want to see, like superheroes and fighting robots, are also pure fantasy and provide ample doses of entertainment and escapism for its audiences.

There will always be a place for films about women yet we are not seeing this enough and one of the reasons is the lack of female directors across all genres; commercial and independent. And while stories about women from the independent and arthouse scene may be considered more important or hard-hitting, that shouldn’t mean lighter, cute and fun stories about women don’t have a place in the hearts and minds of audiences.

The cinema is a place for escape, just as much as it is a place for audiences to reflect on personal experiences, and for an impressionable young girl somewhere in Taiwan, Our Times will probably speak volumes to her and define the kind of stories she would like to see and tell than the litany of “tragic” female stories aimed at more adult audiences.