Written by Brooke Heinz for Japanese Film Festival 2017 in Australia. Filmed In Ether is a proud media partner of JFF 2017.

Video games have had a long and troubled history of being translated onto screen in the West. But in Japan, live-action adaptations of beloved games in recent times has arguably seen more success. While the expected B-movie fare associated with video game movies is still present (one only needs to look at the trailer for Oneechanbara), Japan’s video game films aren’t just great as adaptations; they’re also great in their own right.

Not all hope is lost for video game cinema it seems, but the question still needs to be asked: just how is Japan managing to create meaningful cinematic experiences from their games?

A unique connection to genre: Neko Atsume House and Japan’s slice-of-life

When one thinks of video games ripe for the big-screen treatment, a mobile game might not spring to mind immediately, especially when that mobile game is a simple one-screen cat collecting game. Yet, here we are with this year’s Japanese Film Festival selection Neko Atsume House, an adaptation of Hit-Point’s wildly popular cat-themed mobile game.

With Neko Atsume House, filmmakers had the difficult task of not only keeping fans happy by recreating the relaxed atmosphere of the original, but also creating a story compelling enough to justify its feature-length runtime. Fortunately, Neko Atsume House delivers on all fronts.

Following a decrease in both popularity and motivation, author Masaru (Atsushi Ito) moves from the busy streets of Tokyo to a lonely house in the quiet countryside. While his editor Michiru (Shiori Kutsuna, whose well-timed deadpan humour is one of the film’s highlights) insists he keeps working on his story, Masaru finds himself spending more time befriending an ever-growing number of stray cats.

In criticising the hustle and bustle of city life, director Masatoshi Kurakata highlights the seemingly forgotten value of patience, simultaneously instilling the game’s focus on relaxation and waiting into the film’s visuals, leisurely pacing, and storyline. The inclusion of cats in the film is more than just an obligatory nod to the original source material and they instead represent our often ignored need to rest and discover our own source of happiness. As Michiru says in the film, “You need to learn to be free like these kitties.”

This is all material befitting of the country’s slice-of-life cinema, a unique genre that is deliberately observational in its approach to telling stories about ordinary individuals in ordinary situations. Cinematographer Kei Yasuda’s close-up, handheld montages of the (very cute) cats emphasises the mundane while emulating the observatory joy of both Masaru and players of the original game. Additionally, the vibrant yet naturalistic colour palette of rural Japan brings the colourful graphics of Neko Atsume to life without sacrificing the realism expected of the genre.As a result, anticipate Neko Atsume House’s cinematic stylings to evoke previous Japanese Film Festival slice-of-life selections such When the Curtain Rises.

Embrace the absurdity: Ace Attorney’s faithful recreation

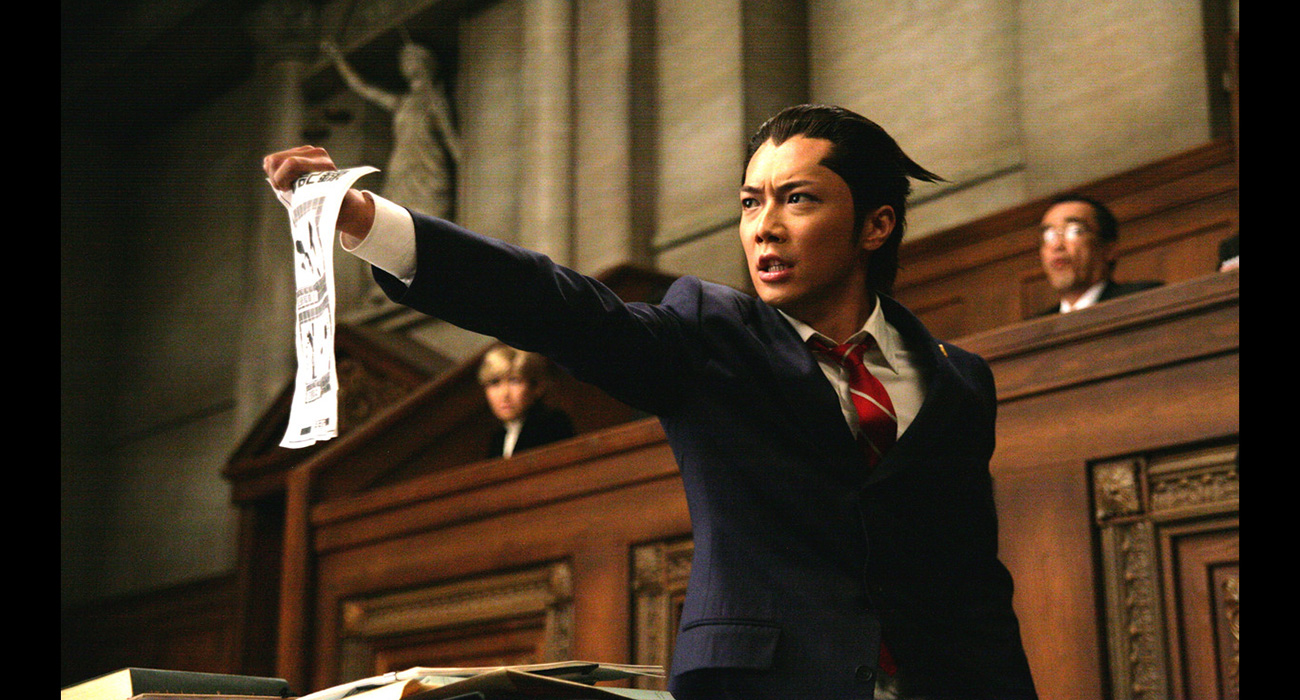

Ace Attorney (2012) sticks closely to the overarching plotline of the Gameboy Advance original, beginning at the conclusion of rookie-lawyer Phoenix Wright’s first murder case.

Following his victory, Phoenix’s mentor Mia (Rei Dan) is found dead at their law offices, with her physic younger sister Maya (Mirei Kiritani) found at the scene. Tasked with defending Maya’s innocence, Phoenix (Hiroki Narimiya) is pitted against highly-respected prosecutor Miles Edgeworth (Takumi Saitō). As each case progresses, Maya, Phoenix, and Miles find their histories are more intertwined than originally thought.

For fans of the games, the above will sound extremely familiar, but the plot is not the only aspect of Ace Attorney which has been faithfully adapted. From the costume design (sans notably, the character Redd White) to whole lines of dialogue ripped straight from the game, there is an attention to detail in Takashi Miike’s Ace Attorney that is truly admirable.

Much of this credit goes towards the cast, especially Narimiya as the titular attorney. His wonderfully pained expression as he struggles to stall for time or offer an objection perfectly communicates the frustration and confusion Phoenix (and likely gamers) felt during their numerous trials. His expressive performance, as well those of his supporting castmates, help inject energy into the film and perfectly captures the silly tone of both the Ace Attorney games and broader Japanese comedy.

However, transforming a roughly 15-hour game into a two-hour film means making compromises. Thankfully director Miike and writers Takeharu Sakurai and Sachiko Ōguchi know when to cut and add to the story. Inconsequential cases, such as the Steel Samurai, are still given recognition with short fan service nods, but their shortening allows for appropriate character development and a more focused storyline overall.

Meanwhile, the societal effects of an overwhelmed court system are cleverly woven throughout, with crowds of media, an eclectically-dressed courtroom audience and oversized, high-tech evidence monitors suggesting the judicial system has become more about spectacle and personality than justice.

As absurd as Ace Attorney can get, it is perhaps the film’s warm embracing of the game’s absurd material that enables it to be so endearing to fans. The live action adaption brings over all the exaggerated humour and compelling mystery of the first game, while taking advantage of the film medium to create a greater sense of progression and world building – making it arguably one of the best video game adaptations to date.

Creating a lasting impression: Project Zero’s loose connections

On the opposite end of the faithfulness spectrum is Project Zero: The Film from horror director Mari Asato. While it shares its name with the PlayStation 2 niche series (also known as Zero in Japan and Fatal Frame in the U.S.), the story is actually based on spin-off novel Zero: A Curse Affecting Only Girls.

Project Zero: The Film transports the haunted setting from a traditional Japanese mansion to an all-girls Catholic boarding school with Victorian aesthetics, where a number of students begin to fall in love with Aya (Ayami Nakajō). After Aya locks herself in her room, her admirers perform a love ritual by kissing her photo at the stroke of midnight. One of the ritual participants, Kasumi (Kasumi Yamaya), is visited by a ghost that looks like Aya before suddenly going missing. Her best friend Michi (Aoi Morikawa) tries to get the bottom of Kasumi’s disappearance as the curse spreads across the school.

As can be gleaned from the plot, Project Zero: The Film has much more in common with mystery-thrillers than horror films. The ongoing mystery behind the curse provides enough intrigue to keep audiences interested while providing a platform for Asato to explore the film’s prominent LGBT+ themes. While much of the anxiety in the Project Zero games revolves around the expectation of a jump scare, the film instead has a lingering tension of the romantic kind between its leads, anchored gracefully by Morikawa’s performance of a teenage girl struggling with unrequited love.

With homosexual themes rarely explored in horror films, Project Zero: The Film doesn’t shy away from the discrimination faced by the LGBT+ community and provides a unique edge.

The slight shift in genre and story are not the biggest changes when it comes to Project Zero’s transition to the big screen. The film does away with the games’ ghost-busting action and instead translates the games’ focus on photography into the film’s own cinematography. Asato’s clever inversion of gameplay mechanics imbues the film with haunting imagery, creating a disquieting atmosphere throughout. A shot of a school girl floating down the river (an intentional nod to the tragic tale of Ophelia) is just one of many examples of Project Zero: The Film’s subtle mixing of the symbolic, quietly disturbing, and emotional. These slow-moving, daylit moments may not provide the shocks fans expect, but they certainly leave a lasting impression.

And in the end, Project Zero: The Film’s decision to subvert all expectation might be its best asset. While it technically involves the Project Zero staples of rituals, photography, and ghosts, this adaptation boldly forges its own narrative and stylistic path to produce a visually engaging film loaded with artistic allusions and social commentary. It might not be exact in its recreation but some of the spirit of the series remains in Asato’s adaptation.

Lifting the ‘video game movie’ curse

From the impressively faithful to the strikingly different, these Japanese films prove it’s not just the degree of resemblance that makes a great video game adaptation – in fact, it can even be the opposite. And in cases like Neko Atsume House, where there is no narrative to draw on, creating one that honours the game and fits suitably within the context of an established genre, it demonstrates that being faithful to a product doesn’t necessarily mean copying it entirely.

Instead, by focusing on developed characters, social commentary, and their own unique tones, each crafts an experience which, to this critic at least, disproves the negative stigma of the ‘video game movie’ label.