ANIMATION

Unsurprisingly, the enduring popularity of anime has afforded many of Japan’s animated films the opportunity to receive international screenings, streaming deals and home releases outside of the country. As a result, a majority of the films mentioned in this category are Japanese and that’s largely based on the accessibility for a lot of these films.

That said, we will endeavour to discover new animation from other countries moving forward but, as it stands, these were the animated titles that really made our decade.

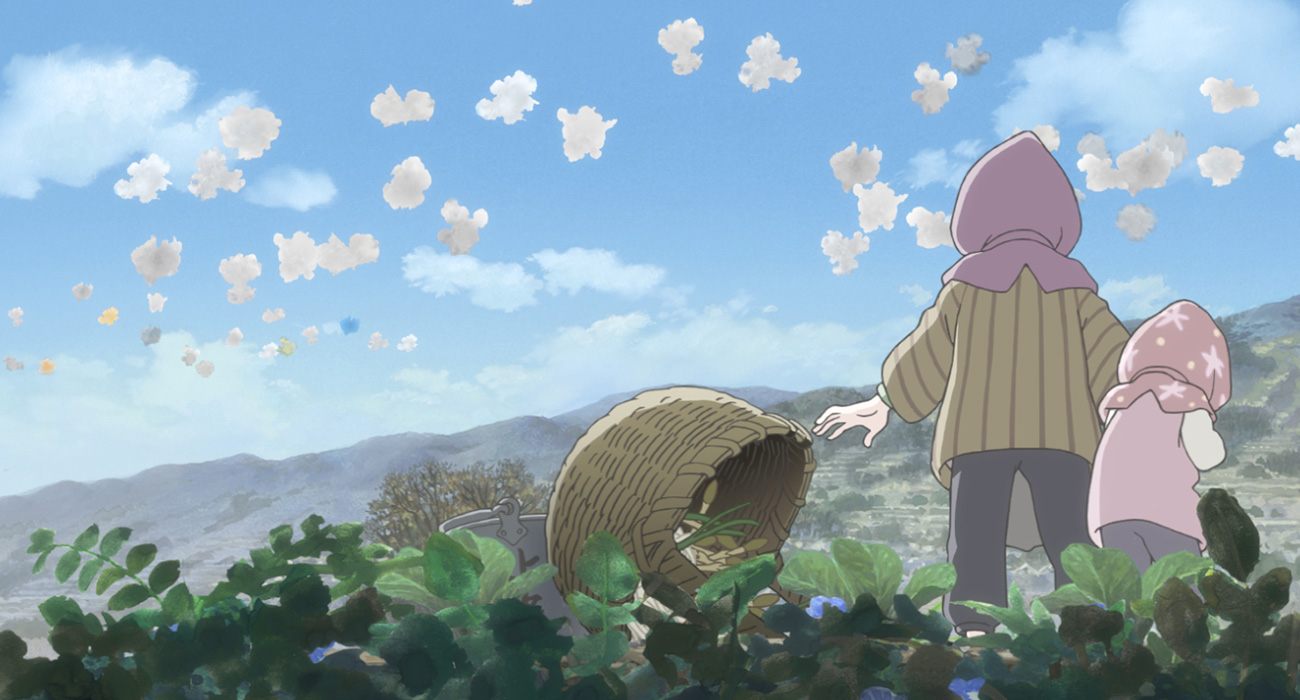

Wolf Children

(2012, dir. Mamoru Hosoda, Japan)

Mamoru Hosoda’s Wolf Children is one of the most delightful experiences I’ve had watching anime this decade. Ghibli inspired without feeling like a shameless clone, Hosoda and co-writer Satoko Okudera weave a fantastical tale of two children born half human, half wolf, and the single mother who attempts to look out for them the best way she can. It leans into its silliness head on, while equally leaning into its deeper societal conflicts, allowing for an equal balance. Finding one’s place in the world, grieving over a loved one, and self-acceptance are all explored with great nuance and complexity, as we follow Ame and Yuki, the eponymous wolf children on their respective paths, having to make a choice between being human or being wolves.

Despite its deep themes, the film is genuinely very funny, featuring many great sight gags, and interactions between Ame and Yuki, especially during their time at school. With a vibrant and impressive animation style, and characters designed by legendary artist Yoshiyuki Sadamoto (Neon Genesis Evangelion), Wolf Children is a beauty from start to finish. Watching the children transition from human to wolf is a sight to behold, and one that I could never get tired of. But after all is said and done, Wolf Children is simply just a lot of fun, and sometimes that’s more than enough. (Amir Muhammad)

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya

(2014, dir. Isao Takahata, Japan)

Studio Ghibli’s output has been consistent excellence for over 30 years. The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, based on one of the most famous stories in Japanese folklore, had been a long-gestating project for the studio under Isao Takahata.

The film is a staggering work of pure art—life-affirming, melancholic, vibrant and minimalist all at once. Takahata and his screenwriter Riko Sakaguchi turn the folktale into a feature length film, using elements of the original story to bring out recurring Ghibli themes such as environmentalism, identity, duty and free will. The art direction of the film looks unlike any animated film out there with spare brush strokes that imitate traditional Japanese art. In one of the most startling sequences, Kaguya runs through a forest in an outburst of emotion. Her figure is reduced to the most minimal of strokes dashing through a hazy black night and yet it is one of the most expressive depictions of unbridled rage and grief I have seen in animation.

In the pursuit of using new technologies to render textures as realistically as possible in animation, the humanity in a piece of work ends up being neglected. The Tale of the Princess Kaguya shows that sometimes, simplicity is best. And as Isao Takahata’s swan song, the film is a testament to his talent and is, in my opinion, the greatest Studio Ghibli film of all-time. (Natalie Ng)

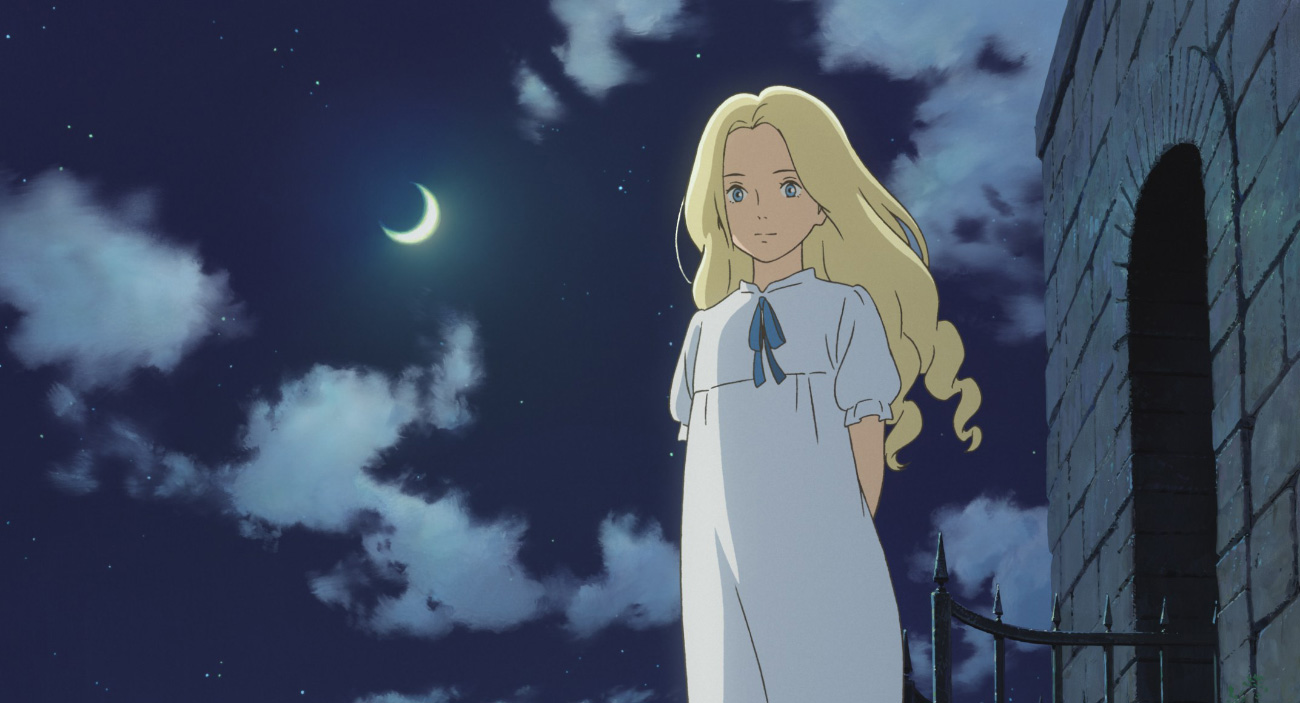

When Marnie Was There

(2015, dir. Hiromasa Yonebayashi, Japan)

What does it mean to be the last feature-length film produced by one of the world’s most beloved animation houses in this decade?

When Marnie Was There might be a curious choice given its scale and ambition aren’t quite as comparable to the final films of Studio Ghibli’s co-founders Hayao Miyazaki and the late Isao Takahata (The Wind Rises and The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, respectively), yet what this modest entry into the Studio Ghibli catalogue does offer could also be considered equally significant.

When Marnie Was There is a promise from Studio Ghibli to audiences that it will continue to nurture talent and strive for continued excellence in a future without Takahata and Miyazaki. Hiromasa Yonebayashi’s gentle film about a young girl who strikes a relationship with a mysterious girl, confidently signals that the future will be in good hands no matter what shape its future films may take.

Farewells might be hard, even for audiences who’ve grown to love the magic of Studio Ghibli, but much like the endings to many of its films, there’s always the promise for an even brighter tomorrow. When Marnie Was There is that promise. (Hieu Chau)

In this Corner of the World

(2016, dir. Sunao Katabuchi, Japan)

Set during World War II, In this Corner of the World ignores military heroes, gunfire, and invasions–looking instead at the lives of those left behind on the shores of their country, wondering if they’ll have enough to eat that day. It is a film about destruction; the relationships that are torn, the bodies that are buried, and the hope that is smashed to smithereens.

It is a powerful reminder that war only serves to destroy and every time we chose war, we choose to upend the lives of ordinary people and we ask them to suffer in service of a grander mission. But is it worth it? I feel the film asks that important question over and over because it must be asked. And most war films never do because they seek to glorify the battles, while Sunao Katabuchi’s beautifully animated film exalts the humble lives of everyday people and their tenacious ability to survive despite immense trauma. (Aidan Djabarov)

Your Name

(2016, dir. Makoto Shinkai, Japan)

Your Name has its place in this list as it makes impeccable use of animation and splendid scenery to take the audience through a story of time travel, teenage years and longing. “That day when the stars came falling. It was almost as if a scene from a dream.” The first lines of Makoto Shinkai’s Your Name introduce us to Mitsuha and Taki watching the same celestial event taking place, each from their own parts of Japan.

We get to know the characters in undeniably funny body-swap scenes where each character has to get used to their new body, scenes that will link to themes of puberty, the city or country life, family and tradition, with hints on gender and sexuality.

Even if the first few scenes are enough to be satisfied about Makoto Shinkai’s take on the time-travel tope, we discover another level to it. Tasogare-doki, “when it’s neither day or night, when the world blurs and one might encounter something not human”, and Kumihimo, the traditional Japanese technique of braiding cords of silk as a metaphor of time intertwining, both become common threads to the story. These carefully chosen details from the characters’ lives elevate Your Name to an emotionally charged journey of finding someone that is dear to you, through space and time. (Claire Langlais)

On Happiness Road

(2018, dir. Sung Hsin-yin, Taiwan)

There are few films that I’ve seen this decade that deal so explicitly and honestly with female failure and disappointment, yet still manage to be a triumphant reflection upon a life. Sung Hsin-yin’s animated debut feature is fiercely ambitious in its scope, attempting to portray the sweep of forty-odd years of Taiwanese history in the space of two hours, and audacious in that it does so through the eyes of a woman and her coming of age.

Yet unlike many coming of age films it avoids sentimentality, resolute in its intent to portray both lead character Chi’s life and the unfolding of Taiwan’s recent history with clear eyes. And it does this with striking hand drawn animation in an era where technology and pixels are in danger of destroying the art form. This film may have been a commercial failure, but as a bold artistic and authorial statement, there are very little to compare with it. (Hayley Inch)