This has been a really difficult for year for so many of us and it’s been especially disheartening to observe the effects the global pandemic has had on creative industries all around the world.

In South Korea, the #SaveOurCinema awareness campaign was launched to encourage local audiences to learn more about out independent and arthouse films by supporting independent cinemas facing financial uncertainty. The campaign was supported by many including actors who’ve broken out thanks to independent productions like Choi Hee-seo (Our Body), Lee Jee-hoon (Bleak Night) and Chun Woo-hee (Han Gong-ju).

Japan also launched two similar campaigns to support its local industry: the #SaveTheCinema initiative and the Mini Theatre AID Fund. The former was a call for help by influential talents, such as Shoplifters’ director and star Hirokazu Koreeda and Sakura Ando respectively, that urged Japan’s government to provide financial relief for the many independent cinemas in the country on the verge of closure due to the pandemic. The latter was a crowdfunding effort organised by established indie filmmakers Koji Fukada and Ryusuke Hamaguchi to directly support independent cinemas, known locally as ‘minishiata‘ or mini-theatres, affected by the pandemic.

In the spirit of these initiatives, we too want to offer what little support we can by pointing you to new film experiences. Every year when we put together these end-of-year reflections, the aim is always to give you a chance to discover something different and find out what’s out there in the world of Asian cinema. Due to the ongoing health crisis, our writers’ summaries and lists of new 2020 content will appear fewer in number than previous years but we hope that there is something here for you both old and new that offers some respite from the exhausting year that was. Now more than ever, please get behind good talent when you see it and, when it’s safe again, go out and support your local film festivals and indie cinemas however you can.

Hieu Chau’s 2020 Film Highlights

Of all the new Asian releases I did watch, none has stayed with me quite as much as Moving On, the debut feature film from Korean filmmaker Yoon Dan-bi. Were it not for Amir’s glowing review of the film and my involvement in putting together Filmed in Ether’s video on emerging South Korean women filmmakers, I probably would have missed this entirely. Yoon’s feature is the perfect blend of minimalism, family drama and coming-of-age and in a better year, I really believe this beautiful indie would have soared to even greater heights around the world. Moving On is my film of 2020.

Very close runner-ups include Han Ka-ram’s Our Body (technically a 2019 release but it never made its way to Australia until this year), a film that struck a deep chord with me in ways I wasn’t prepared, and Ray Yeung’s Suk Suk (now re-titled Twilight’s Kiss for international markets), the story of two closeted gay men in their twilight years who each face their own struggle in coming out.

As for older films that I’ve re-discovered or seen for the first time in 2020, here are a few of my highlights:

-

- Parasite (2019, dir. Bong Joon-ho): After its historic victories at the Oscars, I had to re-visit Bong’s genre-defying film and, no surprises, it still holds up extremely well on a second viewing. Respect!

-

- The Host (2006, dir. Bong Joon-ho): Little did I know that this and Bong’s murder-mystery Mother would be the last films I saw in a cinema in 2020… Melbourne’s famous repertory cinema, The Astor Theatre, held a Bong Joon-ho season following Parasite‘s win and I never realised until now how much of a masterpiece The Host really was.

-

- Petal Dance (2013, dir. Hiroshi Ishikawa): Hiroshi Ishikawa is the king of modern-day minimalist Japanese filmmaking (with a small filmography to boot). Petal Dance is my favourite therapy film. Come back, Ishikawa.

-

- Rashomon (1950, dir. Akira Kurosawa): Kurosawa is timeless and Rashomon is perhaps my favourite film of his I’ve seen so far. The craftsmanship alone… blessed to have seen this for the first time in 2020.

-

- Shadow (2018, dir. Zhang Yimou): Everybody’s a gangster until an army of umbrella warriors slide down on your turf. This was a first time viewing and I loved it so much.

-

- Microhabitat (2017, dir. Jeon Go-woon): “Cigarettes, whisky and you… That’s my only relief. You know that.” This film could have been a lot darker so I’m thankful it went in a more hopeful direction.

Levin Tan’s 2020 Film Highlights

Often I feel overwhelmed by the selections at film festivals – even this year, where programming in the film business has felt the aftereffects of the global pandemic too. It’s this feeling of endless possibilities that has led to the cultivation of my present habit, where I blind buy tickets based off criteria such as ‘not made by a man’ or ‘from a country that I haven’t seen many films from’. Being unemployed really narrowed how many screenings I was willing to attend, so I closed my eyes and let the roulette ball fall where it wanted to.

This inadvertently led me to getting a ticket for Veins of the World by Byambasuren Davaa. Truth be told, the only thing I remembered about the movie before sitting in was what day it showed and what time it started; I even got the venue wrong and only realised once I was on the train. I really went in with no expectations.

The opening shot is exceedingly wide, showing a hilly landscape spread across the horizon as far as the eye can see, enveloped by golden sunlight with a dreamy blue sky hanging above. Then suddenly we see a red car, sports-like in its lack of roofing, kicking up a storm of dust as it tears across the screen. For some reason, right then and there, my gut told me that this was going to be something I’d take home with me.

At its core, this Mongolian film is about commercial mining activities encroaching on its nomad population, but it attaches this motif to a story of a boy racked with grief after his father’s passing. It’s his father who has enjoined his singing since birth, and its this skill that brings him to audition for Mongolia’s Got Talent.

Davaa as a Mongolian filmmaker herself exercises plenty of care in conveying the importance of the land and caring for it to us through a smattering of shots that infuses each blade of grass, whether a lush green or a withered-out yellow, with spirit. This approach extends to her characters too, many who are funny, touching and sincere in both their triumphs and struggles.

Maybe in the line of reviewing and criticism people as audiences might start to wonder what a perfect film looks like – which boxes it needs to tick on the technical and narrative front. I think Veins of the World honestly doesn’t tick some here and there. But a film doesn’t need to be perfect. It might be enough to capture an emotion – a love for something or sorrow over an end – and in its ability to give tangible life to something so spectral by marrying sight, sound and story is a gift that can erode the exteriors of even the most stony cinephiles (or so I hope).

I think I’ll always remember how Davaa had the main character Amra singing the song his father taught him on a broadcast of Mongolia’s Got Talent as she took us on a bird’s eye tour of the Mongolian landscape, telling us about the how our own greed continues to mar the earth. It’s a shot that both leaves you feeling incredibly powerful, perhaps imparting some understanding on ancestral energies that continue to flow beyond perceptions of time and space, and yet at the same time have you wracked with a sense of powerlessness as we come up against a developing world that will always put aside the health of the planet and its carers.

When I came out of the theatre, a random guy came up to me and said, “Cool movie, huh?” I was really caught off guard by that; I was occupied with searching the web about dried Mongolian cheese curds, so all I did was smile and give him an awkward thumbs up.

I’d only intended to mention one film, but a day before deadline I fortuitously managed to catch Melancholic by Seiji Tanaka. This film came out in 2018, but honestly I did not hear of it till now, and purely by chance. Perhaps fate seems to strike twice; I absolutely enjoyed myself.

On surface level, Tanaka’s film isn’t the kind you might immediately take to – in the beginning, his fresh direction rears its head and you can feel some of the rough edges tottering along. Yet somehow the awkwardness actually plays to his favour—and maybe it’s even intentional—as the main character’s bumbling interaction become indelibly seared into your mind for maximum irony and comedy.

That’s the thing about this film: where it may lack in ‘high-level artistry’ (whatever that means), it fills the gap with heartfelt writing and humour so dark that it feels like an endless night. Some more crome-thriller-experienced viewers might turn their noses up at the less true-to-life aspects, but I nevertheless found myself drawn into this constructed world and even a willing subscriber to its entire package of theatrics.

Perhaps it holds a special place in my heart as someone who is also a university graduate, currently unemployed and ruminating over new lines of work (a running joke is: “Why would a Tokyo University graduate want to work in a bathhouse?”). Perhaps I just value the ability of a film to make me laugh, and walk out of the cinema smiling, remembering all the strange and wacky things that occurred. Perhaps I just really liked that it has a Filipino-Japanese actress in it. I could really list a bunch of things, but all I want to do is fantasise about a world where a professional hitman might treat me like a real buddy and then slurp udon with me at my family table.

What’s there not to like? My summary can hardly do this film any justice – best that you go check it out if you can!

Timothy Amatulli’s 2020 Film Highlights

I haven’t even seen enough new films this year to even fill a top ten list. The only new Asian release I was able to catch was Setsurô Wakamatsu’s Fukushima 50, a serviceable but unremarkable account of the 2011 Japanese nuclear disaster. I was a huge fan of Johan Renck’s Chernobyl miniseries last year and hoped that Wakamatsu would be able to capture the same radioactive tension in a comparable disaster, but sadly that was not the case. Fukushima 50 is simply a straightforward biopic starring Ken Watanabe and Koichi Sato, who do a good job headlining the large cast. Overall, however, the film is largely forgettable.

Since I couldn’t see many new films, I made time for plenty of old ones. My main quarantine project has been hosting Sanshiro’s Boys—a 35-episode podcast retrospective of Akira Kurosawa’s filmography. I’d already seen most of his filmography prior to this endeavor, but the one overlooked movie that surprised me the most was No Regrets For Our Youth from 1946, starring Setsuko Hara and Susumu Fujita. It was Kurosawa’s first postwar film, so he was able to artistically express himself much more than he could under strict wartime censorship. This change from his earlier films is immediately apparent and really allows Kurosawa to flex his strengths as an artist and storyteller for the first time in his career.

The decade-spanning narrative is told through the lens of middle-class young adults and chronicles the rise and fall of Imperial Japan with an emphasis on the government’s attacks on free speech and liberal thought. The scale is far larger than any of Kurosawa’s prior works and is emphasized by Asakuza Nakai’s striking visual compositions. Setsuko Hara really shines here in a rare female-led Kurosawa film. He puts her in unique situations that allow her to show more range than she typically does in her collaborations with Yasujirō Ozu or Mikio Naruse. No Regrets For Our Youth is definitely a hidden gem that deserves a closer look from fans of Akira Kurosawa or Japanese cinema in general.

Brooke Heinz’s 2020 Film Highlights

With many of Australia’s major film festivals this year either cancelled, downsized, or just generally devoid of the wealth of high-quality Asian cinema we have enjoyed in recent years, my main sources for the latest films dried up.

Instead, I’ve had to turn to streaming to catch up on some of my backlog of Asian films, with an unintended trend towards Japanese cinema. While not all lived up to expectations, some gems did stand out.

Noriko’s Dinner Table (2005, dir. Sion Sono)

For me, Sono’s films are on a two-point scale of extremes. On the one end, there is what I can only bluntly describe as recklessly violent and sexist trash. But very occasionally, Sono is able to rein in this energy to create films on the other end of the spectrum – films that are delightfully wacky, somehow feminist and philosophical, yet still characteristically perverse. Upon viewing the exhausting Forest of Love, I had almost lost all hope that something on the level of Guilty of Romance or his magnum opus Love Exposure would ever spring from Sono’s mind again.

Thankfully, it turns out going back into Sono’s earlier works was the answer to my worries, with Noriko’s Dinner Table representing a more restrained approach to a truly Sono premise. The titular Noriko is a dissatisfied teenager who leaves her small town for Tokyo, where she becomes embroiled with online communities, families-for-hire services, and mass suicide.

Sono’s surprisingly optimistic musings on identity and self-determination hit me hard, perhaps because of my own crippling depression at the time. Finding empowerment in a Sono film was not an experience I was expecting to have, but I guess anything goes in 2020.

One Cut of the Dead (2017, dir. Shinichiro Ueda)

Also a pleasant surprise is One Cut of the Dead, whose horror-comedy marketing is a bit of a disservice to its heartwarming family-drama tone. A difficult film to talk about given its mid-way pivot, One Cut of the Dead is a clever display of, in a rather meta way, deft low-budget filmmaking—a true love letter to the collaborative craft and social community involved in creating film.

I will leave it at that, as the film is one truly best discovered for yourself. I will warn, however, that for any doubts you have through the film’s first 40 minutes, I urge you to preserve for its unique and highly satisfying pay-off.

Cure (1997, dir. Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

But for a film more in-line with the horror genre, I turn to Cure.

Alongside Hideo Nakata, Kiyoshi Kurosawa is undoubtedly the master of spine-tingling atmospheric Japanese horror, and watching Cure it’s readily apparent that this reputation is well-deserved.

Even at its most basic level, Cure is enough to satiate the taste of thriller fans: an exquisitely crafted detective mystery bolstered by top-tier performances from Koji Yakusho and Masato Hagiwara. But Kurosawa’s attention to detail and his quiet, understated brand of horror elevates Cure to classic status. Come for the brilliant technical filmmaking and storytelling, leave with an elevated heart rate at the sight of ‘x’-shaped graffiti.

Claire Langlais’ 2020 Film Highlights

The number of films I watched this year compared to the watchlist I put together at the start of a lengthy furlough period is laughable, but still, a few films left their mark on me.

Two films I was lucky enough to watch at the cinema were Long Day’s Journey Into Night (2019, dir. Bi Gan), and Flowers of Shanghai (1998, dir. Hou Hsiao-Hsien). Although Long Day’s Journey Into Night’s storytelling was unsettling and I could not quite grasp it (a title card halfway through the film did not improve things either) the film just works on such a visual level that I caught myself thinking about it a few times through the year. I hope to watch it again to fully appreciate the photography and the ever-so charismatic Tang Wei. Flowers of Shanghai is also one that I would love to watch again, although it was already a great opportunity to get to see its 4K restoration. It may feel very slow-paced for some but I felt like it was quite natural for the film, like a slow introduction to characters who would not open to just anyone. For me, a second watch would be perfect to appreciate all the subtleties in the characters’ dynamics and to marvel over how a candle-lit film was so well produced.

Two necessary lockdown films for me would be Little Forest (2018, dir. Yim Soon-rye) and A Simple Life (2011, dir. Ann Hui), both directed by women. Little Forest was the first film of a few that calmed me down back in April, and is about Kim Tae-ri’s (The Handmaiden, Mr. Sunshine) character returning to her hometown to leave the rush of the city behind her. From there, she uses food as a means to reconnect with old memories and relationships. As for A Simple Life, you’ll likely leave this film a little sad but with simple and yet incredibly moving performances delivered by Andy Lau and Deanie Yip, you can tell this isn’t the main goal of the film. A Simple Life is an honest exploration of what it means to age and to care for our loved ones. Although it is a shame that we sometimes find ourselves stuck in a mindset that doesn’t make room for those feelings, films like these can feel like a pat on the back you had been waiting for.

The last two films I found myself very attached to this year were two queer stories: Sisterhood (2016, dir. Tracy Choi) and God’s Daughter Dances (2020, dir. Byun Sung-bin). Sisterhood explores the relationship between two best friends, after the death of one of them. Although one part of the plot is tragic, the film very much feels like an ode to queer relationships, that in a way can be hard to define when looking to do so in a heteronormative society, but essentially, are filled with love and care. God’s Daughter Dances is a short film that follows a transgender woman who is brought into South Korea’s mandatory Military Service Examination for male-born citizens. When Aidan saw the short at Reel Asian, she described it as having “great heart and humour” and I have to agree. Led by Choi Hae-jun, who herself is a transgender dancer, as Mother of the House of Seas, this is a short worth tracking down. I would have loved those two films any year, but with some queer spaces being more difficult to access or engage with this year, it was particularly valuable to find some peace in those.

Natalie Ng‘s 2020 Film Highlights

This won’t be the first time you’ll hear about Moving On, the debut feature film from director Yoon Dan-bi. Popular amongst Filmed in Ether’s writers, director Yoon shines in her intricate writing of relationship dynamics between protagonist Ok-ju and her family and the way she interacts with the world. As Amir covered in his review of the film, the scene where Ok-ju’s fight with her little brother is quietly broken up by her grandfather brought me to tears and is a personal highlight in this beautiful film.

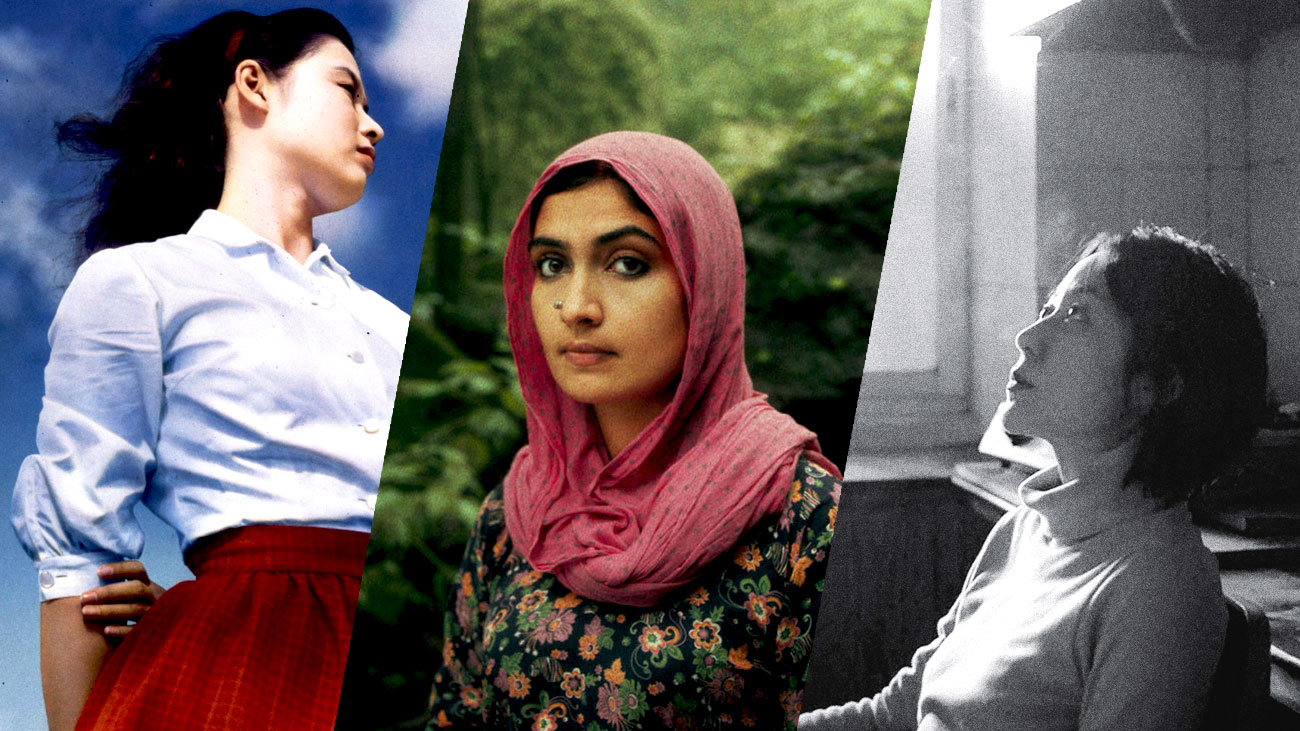

A major highlight for me was discovering The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs, directed by Pushpendra Singh. I chose this film out of the Singapore International Film Festival lineup based on the strength of its synopsis which said it was structured around folk songs. The film is a major technical accomplishment and looks stunning but what makes it really stand out though, is its writing. Inspired by poems written by Lalleshwari, a 14th century woman mystic from Kashmir, as well as a Rajasthan folk story, director Singh updates these inspirations to a present-day setting by placing its story against the beautiful Himalayan mountains in Kashmir and Jammu. Protagonist Laila deals with everyday challenges as a young woman in a patriarchal society, including the classic folktale tropes of men in power lusting after women they know they can’t have. How she navigates them in her own headstrong and sometimes playful ways made it truly a joy to watch. Some have described it as a feminist tale and its not hard to see why based on its absolutely killer ending.

Experimental Works

Through pure coincidence, I got to see two films in cinemas that had “cloud” in their titles. Both were also coincidentally directed by Asian women, could be labelled experimental, and included in Rotterdam’s Bright Future lineup in 2019 and 2020, respectively.

Yashaswini Raghunandan’s That Cloud Never Left is a dreamy hybrid of narrative and documentary that blends old 35mm film reels of Bollywood titles with filmed footage of villagers making toys out of these film reels. You don’t know where the documentary and the narrative begins and ends, and it completely subverts expectations of what film is.

Zheng Lu Xinyuan’s The Cloud in her Room is an impressionistic take on a young woman’s life as she returns to her hometown. Impressionistic style cinema is not new, but director Zheng takes it to a whole new level in this. It’s not perfect, but at the same time it shows her immense confidence and promise in her vision.

Other 2020 highs include The Woman Who Ran, which has Hong Sang-soo going out of his way to obscure male faces (always a plus!); Suk Suk (dir. Ray Yeung), a realistic, tender look at the lives of older gay men; Dear Tenant (dir. Cheng Yu-Chieh), absolutely devastating, you’ll definitely need tissues; and My Prince Edward (dir. Norris Wong), which I wrote an essay on and still marks as my most anxiety inducing film experience of 2020.

Non-2020 Releases

In the early months of lockdown, I decided that it was as good a time as any to explore Japanese New Wave cinema. The director that emerged as a favourite was Yasuzo Masumura, who wasn’t even really considered as part of this circle sometimes because he was a studio filmmaker. And yet, much of his work to me was more transgressive and experimental than other ‘key’ films of the movement. Perhaps it’s because I respond more to character and performance driven pieces, especially his collaborations with the incredible Ayako Wakao. Among his films that I saw this year, my favourites were The Blue Sky Maiden (1957), Red Angel (1966) and A Wife Confesses (1961).

Other films I loved were two films by Masahiro Shinoda: Pale Flower (1964), an exemplary work of Japanese neo-noir, and Double Suicide (1969), one of the most experimental and exciting works I’ve seen that plays with space and staging in cinema.

The best film I saw this year though, was Liz & the Blue Bird (2018, Naoko Yamada). A masterpiece at 90 minutes, the film is astonishing and experimental in the medium of animation both from a technical and emotional standpoint. A small film, it examines the little frissions and intricacies of the relationship between two high school girls as they prepare to play a duet from a piece based on the fairytale Liz & the Blue Bird. Along with wonderful sound design, it also features an absolutely stunning watercolour style animation of said fairytale, along with hand pressed rorschach style paintings the animators used to create animated images of birds flying.

Amir Muhammad’s 2020 Film Highlights

Honestly, what else could be said about 2020? There have been far wiser people with far better words far more attuned to putting those feelings into something poetic, so I won’t try. This year I tried my best to seek out things, and not be complacent in my viewings. On that front, I think I did pretty well! I was given many great opportunities to see films through virtual festivals, of which I am thankful. If this year reaffirmed anything, it’s that so long as we’re doing our best, we’re going to be okay. At least that’s what I hope, but I digress.

My thoughts on Yoon Dan-bi’s touching portrait Moving On are well documented so I won’t rave any further. I will say that with each day that passes since I’ve watched it, my feelings for it and that family have only grown fonder. In a time where seeing family has been limited by a great deal, it was nice to watch a family come together and just be a regular family. No overly hammy acting, no half-assed dark revelations, no severe dysfunction; just a pure family dynamic.

Song Fang’s The Calming—a film I managed to catch during the New York Film Festival this year—is a quiet and honest portrait of loneliness, serving as part travelogue, part character study. In it, a film director having suffered a recent break up begins a journey visiting friends with their new spouses, giving a Q&A about her latest film, and finding inner peace and resolve to keep moving forward. None of this is done in any traditional plot structure or big monologue set pieces. Hell, the boyfriend doesn’t even make an appearance, relieving us of having to sit through those familiar tropes that may have arisen. Instead Song places all her focus and attention onto our heroine’s personal journey cutting all the standard tropes in similar narratives that may have bogged this film down. In doing so, Song instills a tightened control and sense of tranquility rarely felt in films these days. Never has a shot of a woman sleeping on a train (and there are many shots of our heroine traveling by train) been rendered so beautifully.

So what about Main Theme? Well to tell you the truth, the film doesn’t really deal with those kinds of themes previously mentioned, nor does it share any real similarities with Moving On or The Calming. But that’s okay, Main Theme is probably one of the most delightful experiences I’ve had watching a movie this year, an energetic respite from the troubles of pandemic life. Over the course of 100 minutes, Yoshimitsu Morita and his wacky cast of characters bring to life this imaginative little romantic comedy. The plot is thin and features the standard will they won’t they trope, but that’s perfectly okay when you’re treated to wacky magician shows, comic book panels, dekotoras, beautiful shots of the beach and cliff sides, jazzy nightclubs, and a city pop soundtrack featuring songs from the film’s lead actress Hiroko Yakushimaru (who also stars in Kichitaro Negishi’s equally as delightful, equally vibe-y Detective Story, another film that delighted me this year.)

Main Theme unfortunately won’t be remembered in the pantheon of great cinema, but during a year where seemingly everything that could go wrong did go wrong, it was nice to power down, lay back and have a laugh. Think we’ve all deserved that, at the very least.

Aidan Djabarov’s 2020 Film Highlights

Thanks to the virtual Reel Asian Festival format this year, I was able to watch a whole slate of new films and become a fan of many up-and-coming filmmakers. The future of Asian cinema looks bright indeed, and we can expect South Korean cinema to be a dominating force this decade. You can read about my favourites from that festival here. Other new films that I really enjoyed this year were and Heavy Craving (2019) as well as the short film A Woman (2020) whose filmmaker, Tahmina Rafaella, I interviewed.

As for older films that I discovered this year, these were my highlights:

- Comrades: Almost a Love Story (1996, dir. Peter Chan): One of the most romantic movies I’ve seen because of its focus on small, intimate moments that are made to feel as large and grand as feel to the people experiencing them. No surprise, Maggie Cheung’s performance was perfection.

- Kamome Diner (2006, Naoko Ogigami): This film demonstrated kindness just for the sake of kindness, and how it contributes to community-building. So, even if you are far away from home, as long as there is someone who accepts you, you can find a place for yourself anywhere. And how making and sharing food plays an important role in caring for someone.

- The Quiet Family (1998, dir. Kim Jee-woon): Criterion Channel ran a series on New Korean Cinema which allowed me to catch up with this dark comedy starring Song Kang-Ho and Choi Min-sik. Definitely a new favourite of mine in this genre and I’m surprised I had never heard of it prior to this series!

- The White Balloon (1995, dir. Jafar Panahi): One of the best performances from a child onscreen from Aida Mohammadkhani. This film was funny and sweet, but what I enjoyed most was how it subtly showed the diversity of the people living in Tehran which is something not often appreciated by people unfamiliar with Iran. The screenplay was written by both Jafar Panahi and Abbas Kiarostami.