In This Corner of the World is an empathetic and graceful look at the mundane, humorous, and terrifying moments that make up a life lived through war-time. The film is director Sunao Katabuchi’s third feature and is based off a manga of the same name. Katabuchi has been involved in the animation industry for decades and is best known for writing the ultra-violent action manga series, Black Lagoon. His feature films are all period pieces that focus on young women, and In This Corner of the World is no different.

The opening credits lift us into the clouds, where the heroine’s mind often floats. Suzu is a self-professed dreamer and enjoys weaving fanciful tales through drawings she creates to delight her younger sister. Much of the film revolves around the first year of Suzu’s marriage to Shūsaku, a young man she barely knows from a large Naval port city called Kure. Once they marry, Suzu moves in with Shūsaku and his family, and becomes the primary homemaker. She gradually falls in love with Shūsaku, and grows fond of his patient family and the city’s kind residents. At the start of the film, World War II doesn’t seem to inconvenience anyone much. By 1945, the war escalates and air raids begin to occur daily.

As is the case with many war films like this, In This Corner of the World is about sacrifice — specifically those of civilians during wartime. Simply learning to go with a little less; this was a common propaganda slogan from the Japanese government during World War II, with citizens being told “Luxury is Our Enemy”. And with each passing scene, Suzu’s world does indeed become a little less. There’s a little less room to breathe when you’re spending more time hiding in the bomb shelter, there’s a little less paper to draw on and there isn’t much food to eat either. The depiction of Japanese civilians’ modest lives during this period, through all its highs and lows, is one of the film’s key strengths. We see the unthinkable brutality, the hilarity that borders on slapstick comedy, and the tender exchange of kisses between two lonely people. Although some may feel frustrated by the continuous imagery of ordinary civilians embarking on a daily trek to procure rations or civilians coming up with incentive recipes to squeeze the most out scraps, this attention to detail is crucial in illustrating the sacrifices made by these individuals.

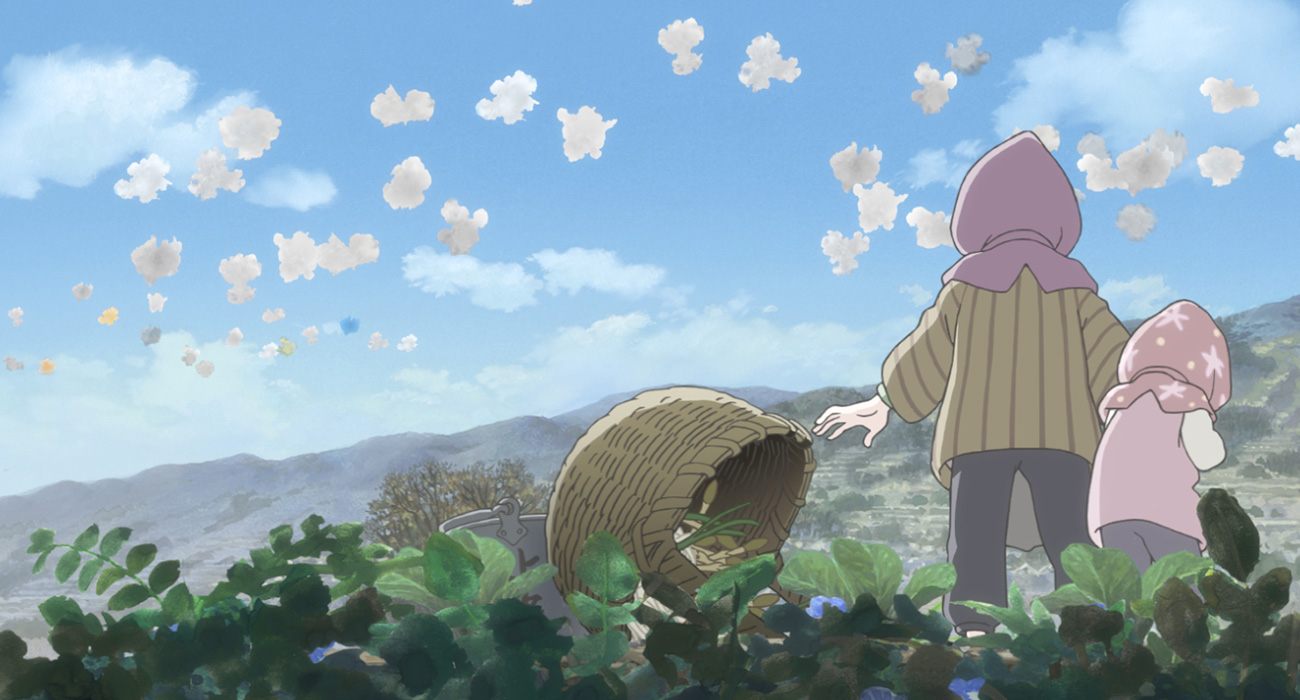

Yet the struggles endured by Suzu and her people can’t falter her cheerful mood and that is perhaps because she looks at the world with an artist’s eyes. In the Corner of this World‘s hand-drawn animation can be viewed as a world entirely created by Suzu’s own hand. We see the story only through her eyes and sometimes the embellishments, especially of Kure’s lush green landscape, reflect Suzu’s style of drawing (if you push this idea far enough, you can excuse the film’s half-sketched supporting characters).

Her observation of an air raid is inter-cut with scenes of paint splashing on a canvas, as she contemplates how she would draw the scene. Other times, we see what could only exist in Suzu’s fantasies. It makes it all the more devastating to handle for her, and the audience, when the film’s colourful frames are replaced by flattened landscapes and mushroom clouds. Suzu’s world becomes greyer, like she’s beginning to run out of paint colours. The most horrific scene is half-haphazardly sketched, with the background, characters and objects only depicted with enough detail to allow us to surmise what occurs without seeing exactly everything. It’s almost as if this moment is too devastating for Suzu to fully realise, so the audience doesn’t either. “I wanted to die a daydreamer,” Suzu thinks, at a point in the film when her reality has become too imposing to escape.

War-time films are often drenched in melodrama and feature exciting action scenes, but In This Corner of the World paints a far more believable portrait than films that do their utmost to wrench every tear from your eyes. An assumed knowledge of Hiroshima’s fate during World War 2 does come into play, especially when when the audience knows what Suzu doesn’t, but the film’s simple message resonates; we endure by the bonds we make with each other. Despite the hardships Suzu experiences, her spirits are lifted not by delving into the abyss of her imagination, but by the people beside her. In one of the film’s final scenes, Suzu will thank her husband for, “finding me in this corner of the world.”

While this question is only articulated at the tail end of the film, it dominates the entirety of it: are the sacrifices civilians make during war worth it? Of course, the film cannot offer a comforting answer to this question but it will nudge the audience every now and then to ask themselves if all that is destroyed by war can really lead to a greater outcome.