In 1985, underground filmmaker, Nick Zedd coined the term “Cinema of Transgression”, which was used to describe a movement comprised of Zedd’s fellow New York-based filmmakers and other artists who incorporated black humour and shock value across their works. In his pioneering article, Cinema of Transgression Manifesto (1985), Zedd claims that transgressive films are made to “go beyond all limits set or presubscribed by taste, morality or any other traditional value system to shackling the minds of men”. In short, transgressive films are produced to break all taboos.

Because of this, transgressive films — or extreme films — are classified harshly in most countries due to its intense and taboo content including (but not limited to) extreme violence, eroticism, sex and extreme vulgar language. With this in mind, you’d be forgiven in thinking that conservative countries would steer clear of controversial subject matter yet transgressive cinema continues to be a thriving filmmaking scene, particularly within Japan.

In fact, the rising popularity of Asian extreme films have furthered the growth of the genre, evidenced by such imprints as the Asia Extreme label which U.K’s Tartan Film distributed throughout the 2000s; a label which sought to meet the demand of consumers hungry for the extreme. Under this banner, Japanese directors such as Takashi Miike, Sion Sono and Yoshihiro Nishimura thrived, found success abroad and have have continued to contribute to the growth of this niche genre.

Beyond those modern names, Japanese filmmakers have long produced films that were far from normal ever since the 1950s. During the ’60s and ’70s, Japan’s cinema of transgression hit its stride and became popular with Japanese audiences, especially once two of Japan’s oldest studios, Toei and Nikkatsu, began production on a large swath of these films. One of the most controversial films produced in this “J-Exploitation” era was director Morihei Magatani‘s The Bloody Sword of the 99th Virgin (Kyujuyuhonme no Kimusume), which contained several debatable scenes including a scene where hanged young girls are brutally murdered by a ‘holy’ sword by superstitious natives. Moreover the film received initial backlash in Japan for its depiction of locals from the Iwate Prefecture and thus has seldom been screened in a local Japanese cinema.

As the J-Exploitation genre flourished, independent film studios saw an opportunity to take these often violent films further by incorporating strong elements of gore and horror with eroticism, thus creating a whole new genre: the Pink Film (or pinku eiga). Major studios like Toei and Nikkatsu again capitalised on the trend, producing a series of Pink Films that emphasised on highly sexualised content. Toei would go on to launch its own subgenre of Pinky Violence while their other major counterpart, Nikkatsu birthed the Roman Porno; both were instant hits in Japan and took Japanese cinema by storm.

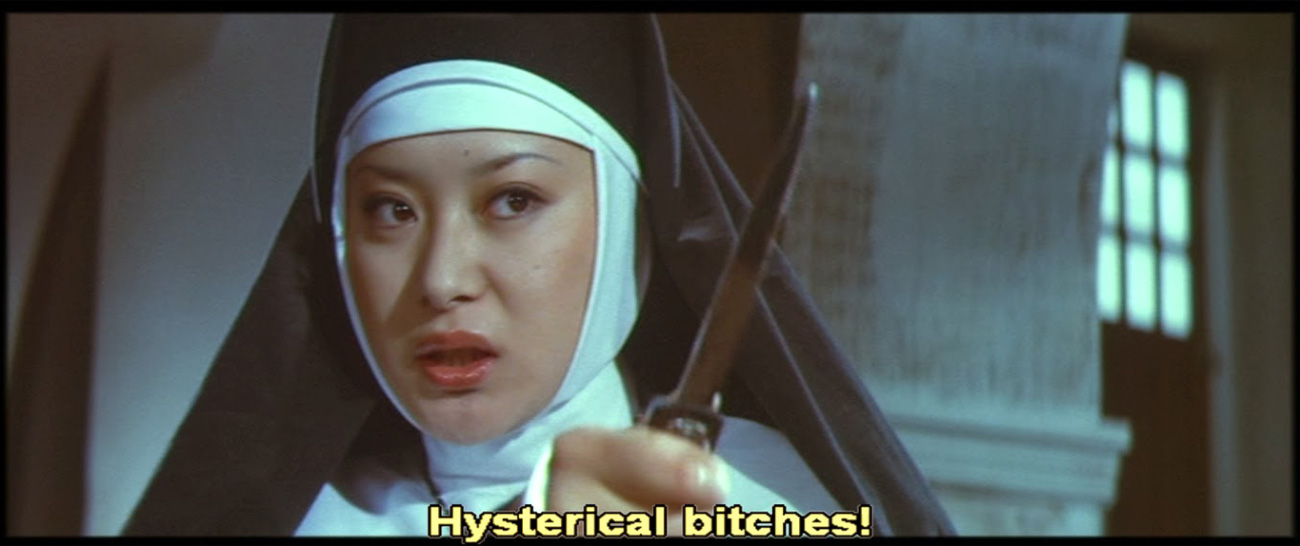

One of the most acclaimed of Toei’s Pinky Violence Films is none other than Norifumi Suzuki’s School of the Holy Beast (Seiju gakuen) which started the notorious “nunsploitation” trend within Japanese extreme cinema. The film featured hyper-sexualised and explicit torture scenes revolving around a disturbing masochistic ritual carried out by perverse nuns. The graphical depiction of the bloody whipping scenes, the film’s lesbian undertone as well as its horrific scenes of religious blasphemy were all highlights of the film that made it a masterpiece of its genre.

While Japanese filmmakers were granted an enormous amount of creative freedom — exemplified by the above films already mentioned — and were encouraged to be as imaginative as possible, there were still some things that couldn’t be transgressed. The Japanese emperor, for example, was a touchy subject and couldn’t be portrayed in a negative light causing filmmakers to tread carefully. Going further back, film depictions of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were also highly scrutinised, and forbidden in most cases, during the Allied Nations’ occupation of Japan. Though filmmakers were more free to talk about the bombings in post-occupied Japan, it was still a sensitive topic.

In 1969, director Teruo Ishii released The Horror of Malformed Men (Edgoawa rampo zenshu: Kyofu kikei ningen), notorious not just for its thrilling story of a man’s shameful family past (which involved incest, murder and madness no less) but for the public reaction surrounding it. In the film, human subjects of a mad scientist undergo unorthodox surgery and chemical treatment which ultimately turns them into deformed monsters. Given the country’s history with nuclear weaponry and the resulting fallout from it, public perception of the film as being offensive towards the disfigured as well as its title, which in Japanese was considered strongly derogatory, led to its swift ban.

While many mightn’t be so quick to accept the controversial and disturbing contents portrayed in such films, there is an appeal to these extreme titles in that these works are often more original, interesting or challenging in nature. And with the creative freedom that filmmakers are afforded in making these films, they are able to at once challenge traditional societal expectations while offering audiences an extraordinary cinematic experience that’s not always illuminated in mainstream media. Transgressive cinema has certainly evolved a lot over the years but what it hasn’t lost is its power to shock and break taboo. Who knows where Japan will take its brand of extreme transgressive cinema next?