Somebody once told me that art reflects society and that cinema portrays what society demands. To understand where contemporary Korean cinema is today and how some of its most famous (or infamous, depending on your perspective) films have also been its most extreme, one must first understand the unique history behind the country’s film industry.

Today, the South Korean entertainment industry can stake its claim as an Asian media powerhouse but it wasn’t all sunshine and rainbows for the country which has experienced a turbulent history. Korea was annexed by Imperial Japan (from 1910- 1945), the South was invaded by the North leading to the Korean War and was subsequently dominated by military dictatorship. During all these important periods of South Korean history, filmmakers were not only heavily suppressed but made to utilise their talents to produce propaganda films, manipulating public opinion for years before the South was finally freed from the despotism.

After years of hardship under military rule, the South Korean film industry saw a revival in 1995 along with the dismantlement of the previous government’s censorship board. Since then, the Media Rating Board — made up mostly of local experts across various film disciplines — had taken over which granted South Korean filmmakers a greater amount of freedom to produce films that would inevitably resuscitate their domestic cinema. And just like that, the cinema we consider as “Contemporary South Korean Cinema” was born along with renaissance of Korean extreme films, hence, signifying the boom of the local film industry.

With the amount of freedom granted, the seed of creativity that laid dormant within the South Korean film industry began to flourish. Gifted filmmakers were finally given the chance to be experimental with their filmmaking, and in particular, to express their years of adversity under the suppression of dictatorship. It is perhaps no surprise then to find that Korean extreme cinema is often filled with dark films that — as Kim Kyu-hyun wrote on his essay ‘Horror as Critique in Tell Me Something and Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance” — openly challenge and criticise “the cultural conventions and ideological strictures imposed by ‘mainstream’ Korean society”.

Indeed, Korean extreme cinema is filled with dark, twisted films that reflect the ugly truth about modern South Korean society and one of its biggest visionaries, director Park Chan-wook, is just one example of a filmmaker chiefly known for works that have exemplified the very qualities that earmark Korean extreme cinema. His notorious Vengeance Trilogy includes three transgressive films that revolve around the theme of revenge: Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002), which exhibits the subject of illegal organ trade; Oldboy (2003), which explores the issue of false imprisonment; and Lady Vengeance (2005) which portrays a menacing tale of exonerate convicts.

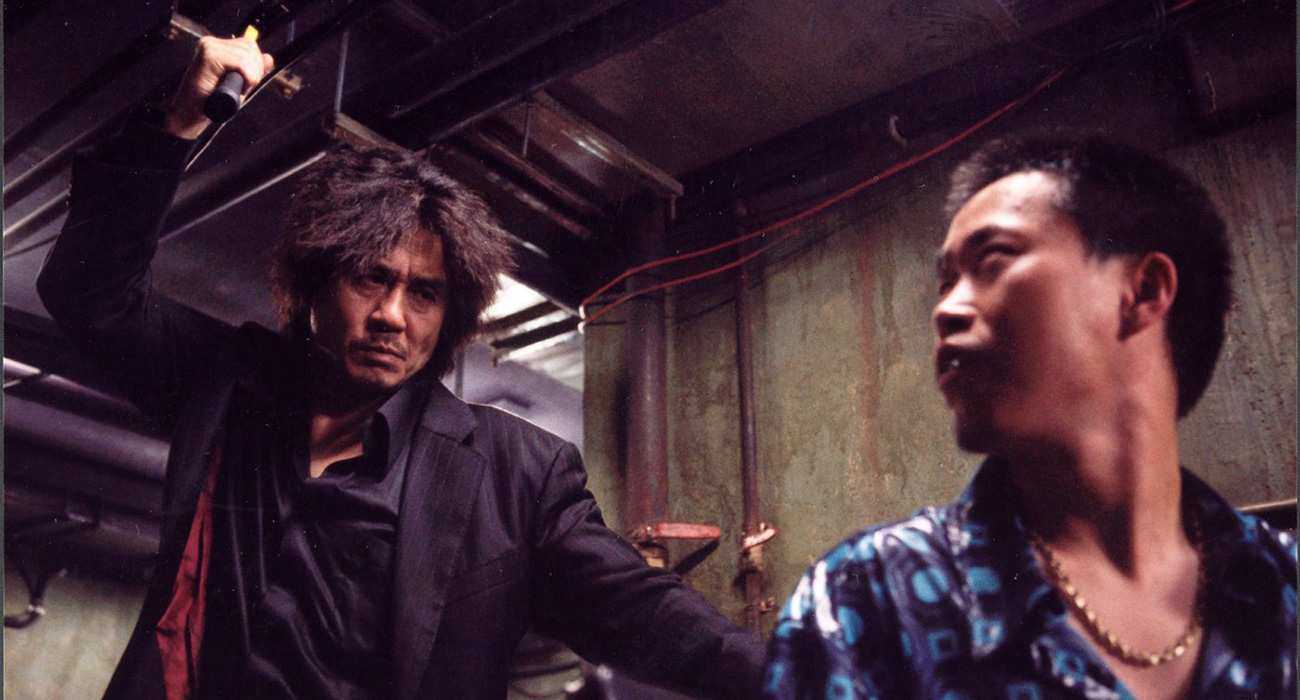

While all three films in Park’s Vengenace Trilogy exhibit a similar pattern (twisted protagonists mistreated or wronged by society), Oldboy is arguably the director’s strongest (or at least his most well known). Oldboy revolves around Oh Dae-su, an ordinary businessman who is kidnapped and locked away in a tawdry hotel for 15 years without a reason. When he is finally granted freedom, he vows to uncover the motive behind his imprisonment. Driven to madness, Dae-su kills and tortures just about anyone standing in his way to find the truth.

Filled with grotesque torture scenes and a perverse story that leads into one of the most jaw-dropping twists in Korean cinema, it’s the film that put director Park on the map. The poetic style of Oldboy made him one of the most critically acclaimed cult directors working within extreme violence and his dark directorial style would lead to the kind of cinema that Park has continued make for audiences — dark, disturbing and often deranged.

Park is not alone in his critique of Korean society. Other filmmakers including Bong Joon-ho (The Host, Snowpiercer) and Na Hong-jin are famous for using their stylishly dark films as vehicles for commentary, most often by way of black humour.

One such example includes director Won Shin-yun‘s 2006 extreme and black comedy, A Bloody Aria. In the film, director Won tackles the contemporary manifestation of bullying by exploring controversial societal issues such as sexual harassment, overt bullying as well as the ideology behind a hierarchical society.

A Bloody Aria has a pretty straightforward story plot: an ambitious opera singer, In-jeong, flees into the secluded woods after her music professor, Yeong-seon tries to rape her. However, she soon finds herself in deeper trouble when she is halted by the leader of a thug group, brought to a riverbank where she meets an injured boy, Hyeon-jae, only to then be reunited with Yeong-seon. In the film, director Won constantly switches the roles of victim and aggressor, presenting an agonising moral dilemma in front of the spectators’ eye that make viewers question the basis of human morality.

For instance, we first see Hyeon-jae as a victim when he is brutally bashed by the group of sadistic thugs in the film and we sympathise with him when he tells a story of how he was made to swallow a living rat and forced to eat food with spit in them. However, he soon switches from the victim’s role to the abuser’s role when he tries to burn the thugs alive after burying them into the ground and pouring gasoline onto their head.

It is at this point that we begin to feel some sympathy towards the thug’s leader, Bong-yeon especially once we learn that he was once a victim of bullying in school and that his reasons for abusing Hyeon-jae were out of vengeance against Heyong-jae’s brother who was the aggressor from his perspective. A Bloody Aria lets the audience consider who really are the protagonists and antogonists of this film and, on a larger scale, forces the audience to consider who the heroes and villains are in everyday life.

While issues with censorship in Korean cinema has largely grown more lenient, problems still exist. Today, the biggest censorship taboo largely stems from the exhibition of genitalia which is strictly prohibited from public screenings. Jang Sun-wu‘s controversial Lies (1999) was one such film that did just that, resulting in a swift ban and its screenings pulled from cinemas nationwide.

Despite its controversy however, the film — which depicts the sadomasochistic relationship between a 38 year old, J, and 18 year old, Y — managed to explore issues of extramarital affairs and underlined the problematic rape culture in society. In the film, Y is depicted as a high-school senior who wishes to lose her virginity “the normal way” instead of being raped as her sisters did. Consequently, she loses her virginity to J, a married, middle-aged-sculptor just minutes after getting to know him.

Their relationship — which is chiefly filled with imagery of sexual deviance throughout the film — is made particularly disturbing through director Jang’s cinéma vérité style. Coupled with the narration and intercuts of interviews within the film, Lies is made to be feel unbearably realistic which is perhaps another reason as to why it was effectively banned despite the commentary it tries to invoke.

While Japan’s transgressive cinema is filed with visually shocking films, Korean filmmakers on the other hand are a little more virtuoso in their approach; producing dark, eerie and disturbing films that speak volumes of the society they inhabit. Unquestionably, contemporary Korean cinema has become one of the leading flag bearers of the Asian Extreme label.